Worlds on paper:

Letterpress artist Kelvyn Smith brings poetry to the print process using inks made with algae

Smith has specialised in letterpress and moveable type for the entirety of his career and has an affinity for working with forms invisible to the naked eye.

In letterpress, he explains, the final image is the product of physical furniture and grid systems measured in picas and points and forged in steel. Even the negative space, the areas where ink is absent from the page, is created with physical objects on press–weighty slabs of lead whose physical heft is erased by the printing process.

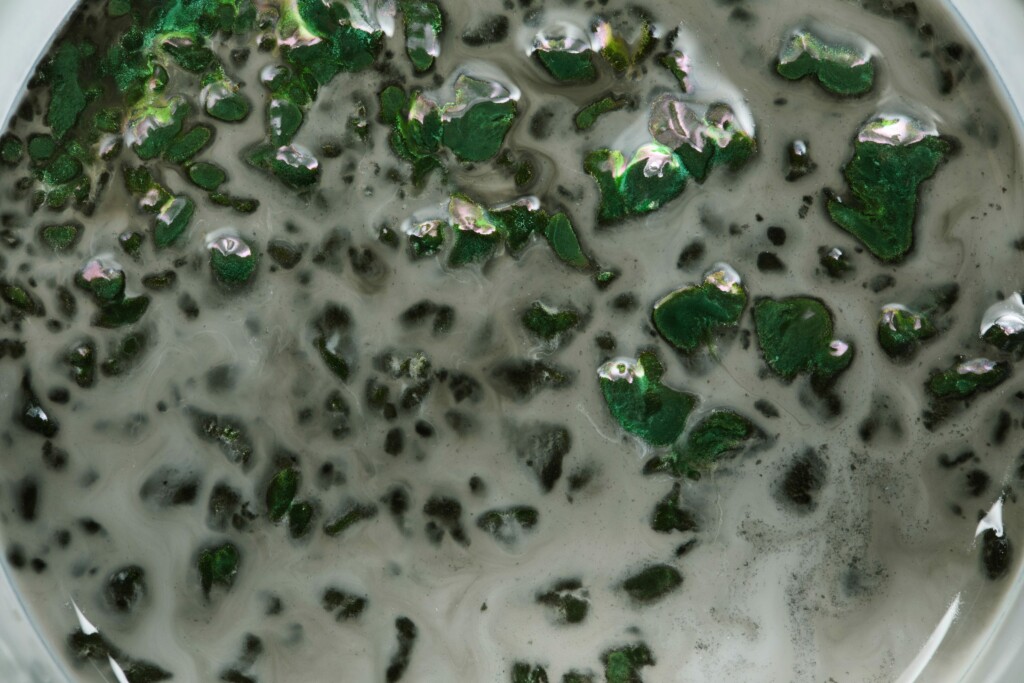

Which is fitting, because the ink he’s about to apply to an arrangement of super-condensed letterforms is unlike any he’s used before, and is the product of microorganisms all too often overlooked. It’s an algal ink, manufactured from the waste-biomass of millions of algae cells–a byproduct of a natural blue food colourant production called phycocyanin–but it has the same depth of colour, viscosity and weight as its petroleum-based alternative. And it prints beautifully, says Smith.

It’s the invention of Scott Fulbright, a microbiologist and the co-founder of Living Ink; the result of years of immersion in the microscopic world and a more recent obsession with the carbon-based pigments that surround us on every printed surface imaginable. What if, Fulbright wondered, the most ubiquitous life-form could be used to replace one of the most ubiquitous carbon-based products and rule out the need for petrochemicals in all manner of inks and dyes?

“You can’t see it with the naked eye, but the microscopic world is full of love and hate and competition and collaboration. Everyone’s just trying to survive.”

Predominantly aquatic, photosynthetic organisms, algae proliferate the known world, ranging in scale and complexity from microscopic single-celled Micromonas, to 200-foot long kelp. Whatever their size, they are always at the bottom of the food chain; an important, if overlooked, place to be. Algae feed plankton, plankton feed fish, fish feed ‘higher organisms’ like us. No food, no complex life, no wider ecosystem, no meditation on our fragile existence, absolutely no art.

Algae probably don’t spend much time meditating on the importance of their oxygen production to the existence of moveable type, but put a microscope on top of them and there’s an abundance of biological complexity to be found. “Looking into the microscope is like entering a whole new world,” says Fulbright, “one that surrounds us all the time. You can see cells dividing in front of your eyes. Tiny forms that look like Pac Man coming along and just ripping up algae, or small eukaryotic organisms engaged in a fight. You can’t see it with the naked eye, but the microscopic world is full of love and hate and competition and collaboration. Everyone’s just trying to survive.”

Nevertheless, many of Fulbright’s postgraduate peers at Michigan State University derided him for his area of study. “There was a hierarchy,” he explains. “You had dolphins and lions at the top, then at the bottom of the food chain there was pond scum, and that’s what I was studying.”

But that pond scum has become a topic of huge importance in recent years. As our understanding of algae has increased and its life-giving qualities fully recognised, we’ve simultaneously been forced to reckon with its destructive potential too. Fed by the run-off from industrial agriculture, algae has the capacity to reproduce at incredible speeds and to such an extent that it chokes waterways, creating dead zones where no other aquatic life can survive. This process, known as eutrophication, has become commonplace around the world (there’s a dead zone the size of Connecticut in the Gulf of Mexico), but thanks to Fulbright’s dedicated attention to smaller life-forms, we’re now able to use these excesses of algae for creative ends.

Now Smith is rolling the product of all of Fulbright’s wondering across an arrangement of wooden type that represents algae’s life-giving oxygen production and pays homage to the vital work the microscopic world carries out unseen. Each time we inhale, roughly 50% of the oxygen we draw into our lungs was produced by algae. It’s a fact that Fulbright drops into every talk and presentation he’s asked to give. And with good reason; it captures the imagination. So much so that Smith has spent weeks sketching and test printing to find the best way to represent this simple truth in a work of art.

His solution is a triptych of prints featuring row upon row of uppercase ‘O’s arranged to resemble the man-made lakes used for commercial algae production. Not only that, but “the amount of oxygen they produce is represented by the amount of type on page.” It’s a detail that goes unseen without close inspection, but one that brings both Smith’s inner world, and the microscopic world, to life.