Waste Made

Concrete:

A portable lamp offers a blueprint to clean up the mess of global construction.

While the vast majority of people in the global north are accustomed to managing and recycling domestic waste as part of their weekly routines, and a vast infrastructure exists to repurpose it into new materials and products, the same cannot be said for the construction industry, which in Europe accounts for 35% of all waste produced—some 850 million tonnes annually. To date, recycling initiatives in the construction industry have yet to be implemented at scale.

In addition to all the waste, global construction faces a twofold problem with manufacturing new materials. First, the production of Ordinary Portland Cement (OPC)—humanity’s second most in-demand substance after water—is a heavily polluting process. Limestone is burned at 1400 degrees Celsius, which requires a huge amount of fossil fuel-based energy and releases additional carbon dioxide as the limestone burns. Carbon emissions from construction materials account for 11% of the global total. Simultaneously, the world is running out of the raw materials used to produce OPC. Sand and gravel are in diminishing supply and their prices are currently at a premium.

Could Biocement be the answer to all these problems? An increasing number of technology companies and manufacturers believe so, including Biomason in the US, and Front, formerly StoneCycling in The Netherlands. Both have been valuable collaborators on NPOL’s latest NPOL Original, the Gathering Lamp, a desk lamp made from cement engineered by microbes.

“You can use design to push for transformation and to find opportunities to make things better across all kinds of different scales.”

A household product as seemingly insignificant as a desk lamp might not seem like the obvious answer to such a colossal global challenge, but it has the potential to galvanise people around new practices and modes of production, says Ioana Man, lead designer at Faber Futures. “You can use design to push for transformation and to find opportunities to make things better across all kinds of different scales.” And people need to be mobilised, agrees Ward Massa, co-founder of Front, particularly in the construction industry where a conservative mindset and short-term focus on profit makes it harder for startups like his to break into the market.

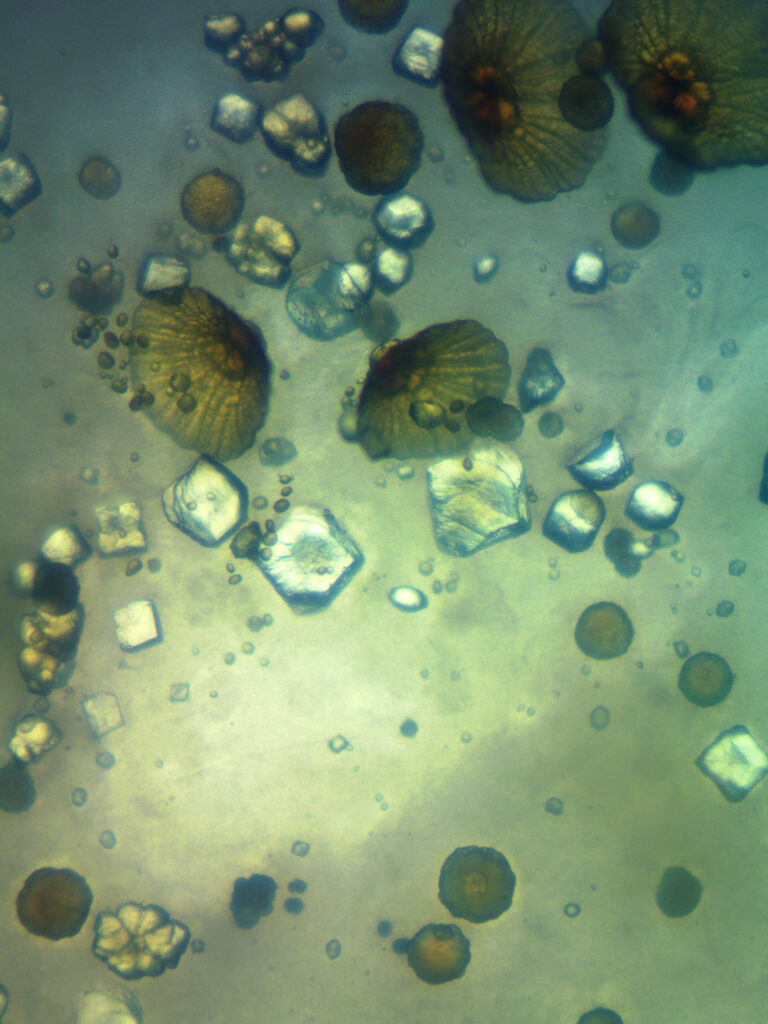

Biocement is biofabricated by mimicking a process common among aquatic organisms. “Our oceans teem with life forms that rely on biomineralisation for their existence,” explains Lauren Donnelly, head of technology transfer and field operations at Biomason, whose technology is key to a transition away from OPC. Coral serves as a prime example. “Coral’s ‘skin cells’ construct a calcium carbonate shell, providing essential protection.”

In Biomason’s biocement, instead of bacteria secreting calcium carbonate around dead organic matter, bacteria are used to calcify crushed waste materials like granite from the construction industry, turning vast quantities of debris destined for landfill into a viable, scalable new form of cement. Biocement can be made using a wide range of waste materials and aggregates, and the biogenic process that cures it takes place at ambient temperatures, meaning no burning or mining is necessary for its manufacture.

Biomason’s proprietary technology is used by startup biomanufacturers around the world to make products specific to their local needs. In the case of Front, that includes a range of standardised biocement tiles, now commonly used for flooring in large retail outlets in public spaces, and at the bespoke end of the spectrum, as a key component in ambient desktop lighting. The range is growing and diversifying as fast as the technology will allow.

We need to speed up this transition,” says Ward, and smart design is where he believes this acceleration can begin. By using biocement in consumer-facing products like the Gathering Lamp, Ward hopes “to inspire other people to use our products in all kinds of ways that change prevailing narratives. Design is a great way to change the hearts and minds of people.”

“We just drilled two holes in each tile, and that’s literally all of the material that gets displaced. You don’t fuck with the tile. Changing its shape might have made things look more interesting, but then you take the timelessness away and add complexity to the manufacturing process…”

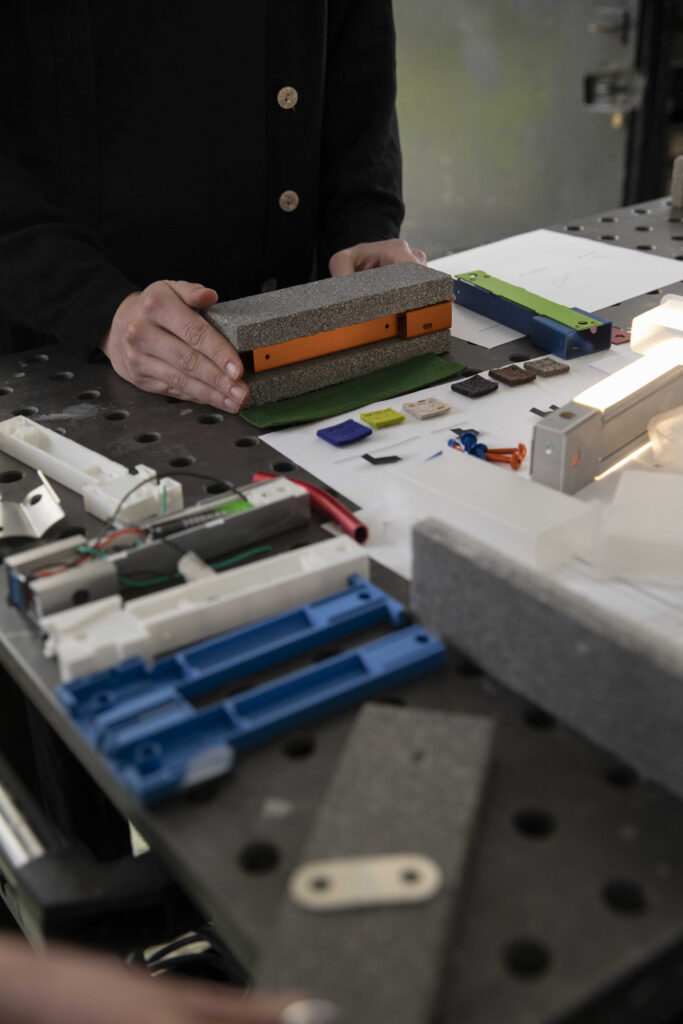

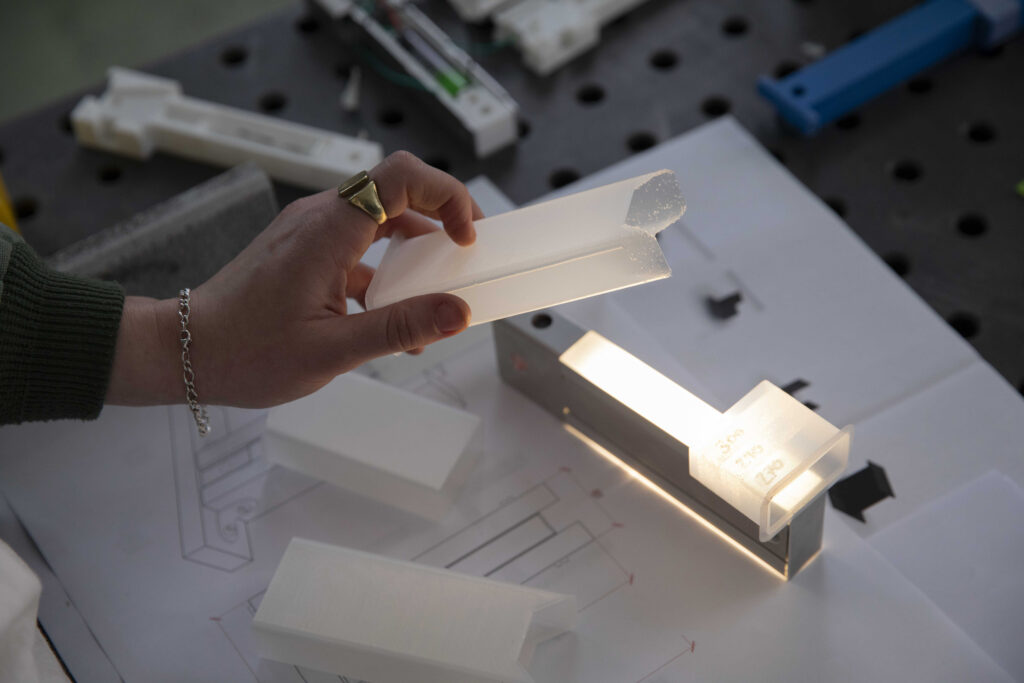

So to the lamp, a modular product fashioned from uncut, standardised Biocement tiles fixed and fitted with a range of custom-designed and off-the-shelf products carefully chosen for their circularity. Throughout the design process, Ioana had one guiding principle, “you don’t fuck with the tile,” which comes in a predetermined size and shape. While initially tempted to cut it or add curves to soften its hard edges, both of those interventions would have created waste material, detracted from the tile’s innate form and, Ioana believes, otherwise distracted from the product’s singular focus on reducing waste with biodesign. Instead, the material shaped the design direction.

“We just drilled two holes in each tile, and that’s literally all of the material that gets displaced,” she says. “Changing its shape might have made things look more interesting, but then you take the timeliness away and add complexity to the manufacturing process, which means you lose the design values. It’s a fine balance between manufacturing constraints and beauty.”

To achieve that balance, Ioana worked closely with Josef Shanley-Jackson and his team at Mitre and Mondays, a design and manufacturing studio specialising in “designing for disassembly.” This methodology exclusively uses recyclable products already in mass-production in adjacent industries (the anodised aluminium bolts that secure the lamp are commonly used in in motorcycle production) or creates custom products and objects from scratch, embedding circularity into each stage of their design—not an easy thing to do where electronics are concerned.

"Consumer electronics are incredibly wasteful and don't fit very easily into the circular narrative. But with the Gathering Lamp, we've created something that allows each component part to either be repaired and replaced, or sent back to the manufacturer to be recycled."

“Consumer electronics are incredibly wasteful and don’t fit very easily into the circular narrative,” says Josef. “But with the Gathering Lamp, we’ve created something that allows each component part to either be repaired and replaced, or sent back to the manufacturer to be recycled.”

Led by Ioana’s design direction, Josef’s team worked through numerous iterations to arrive at something that celebrated the singular form of the tile. “There’s a real clarity of thinking when you’re showing someone a new material, but in a form that they recognise,” says Josef. “We’re not trying to overload too many ideas into a single object.”

“It’s a rectangular tile, so the lamp is going to look minimal,” says Ioana, but it breaks free from the hard industrial-modernist feel one might expect from a concrete product by virtue of the way it modulates light and casts shadow over its surroundings. Unadulterated by any adornment, the design gives the biocement material plenty of room to shine. And as the first in a series of products and home furnishings made from this new form of concrete, the intention is that the lamp forms the focal point of a growing collection around which people can gather to enact a more biophilic future.