TECHNOLOGY

TECHNOLOGY

NPOL is nurturing a new materialism for products grown with biology.

“Our planet is alive with data!”

This decades-old IBM slogan is indicative of the conceptual shortcomings of Western ideology, industry and economics in the last half century: The products and technologies we have chosen to interact with the most are all engaged in the translation of our biological existence into a string of binary code, and we confuse that data with the stuff of life itself. It’s not data that gives the planet life but the billions of different lifeforms it plays host to–everything we make and do is a product of that organic, living world.

As economist Kate Raworth notes in Doughnut Economics, her radical reimagining of economic systems to fit planetary constraints; “The Economy exists within the biosphere, that delicate living zone of Earth’s land, waters and atmosphere. Everything that is produced–from clay bricks to Lego blocks, websites to construction sites, liver pate to patio furniture, single cream to double glazing–depends upon this through-flow of energy and matter.” However much the smooth screen of our smartphones entreats us to believe otherwise, we are still just flesh and fat, blood and bone.

“The Economy exists within the biosphere. Everything… depends upon this through-flow of energy and matter.”

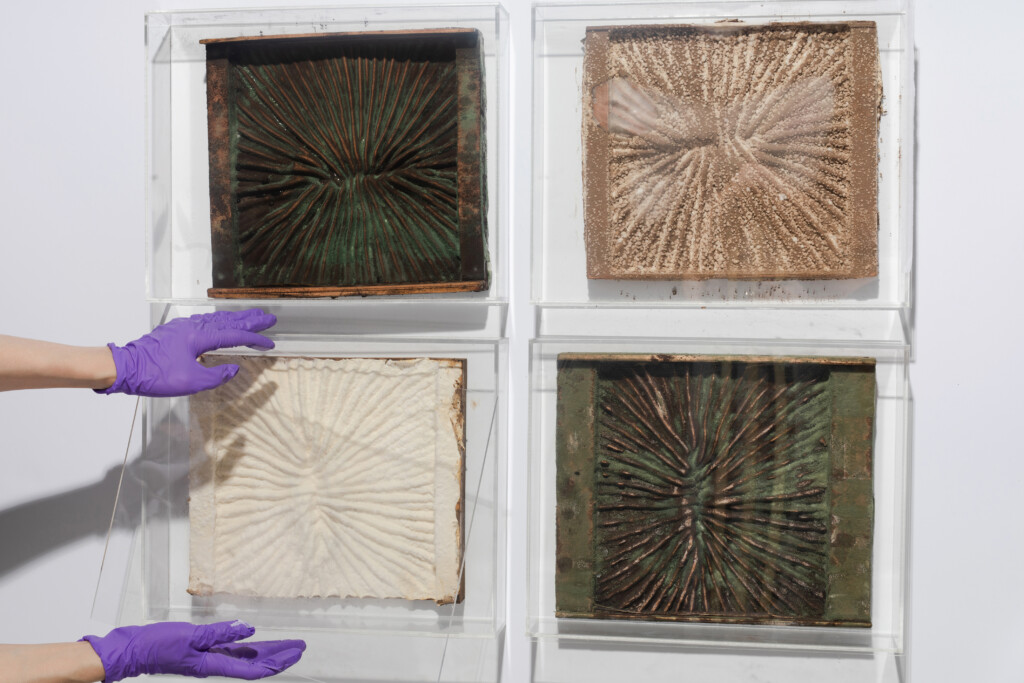

Normal Phenomena of Life (NPOL) exists to put biology back at the heart of the goods we make, the supply chains we build and the economies we choose to scale. To supplant those industries grown on the promise of limitless petrochemical-powered growth and to honour the fact that nature is the original technology. It does this by bringing together a range of bio-based products–inks made with algae, garments grown and dyed with bacteria and furniture repurposed from waste with the help of ingenious microorganisms–that have the potential to repair our broken relationship with the natural world and reject the idea that technological progress can’t prioritise soft cells over hard steel.

The collection represents only the first flush of fruits from new biological technologies and interdisciplinary collaborations, born out of knowledge and process sharing between designers, biologists, materials scientists and other practitioners whose disciplines have yet to be named.

It hasn’t been easy to get here. The most defining feature of the natural world is its reluctance to be easily tamed–and with good reason. Nature, unlike humanity, is respectful of boundaries. In a lab, under exact conditions, cells can be coaxed into exponential growth. A single E.coli cell could replicate itself to 22 times the size of Jupiter given only 48 hours and enough sugary broth. But take it out of the petri dish and those same E.coli cells propagate at much slower speeds. That slowness is essential to our survival.

Designing with biology, and with boundaries, then forces us to reconsider every aspect of the discipline’s paradigm, moving us away from the rapidly-scalable industrial processes that have defined the 20th century and into a network of interrelated systems, processes and supply chains that are slower-paced, scaled to fit, heterogeneous and thus more resilient.

“Nature isn’t homogenous,” says Faber Futures CEO and NPOL co-creator Natsai Chieza. “Nature doesn’t necessarily want to make a brick that you’re not going to notice.” Nature has its own practices and processes, refined over 3.7 billion years, and nature has its own aesthetics too. If the goods sold at NPOL look like nothing else you’ve seen before, that’s because they’ve been imagined and created with that new paradigm in mind.

An economy designed in partnership with nature requires nothing short of “a fundamental reimagination of the world,” says NPOL co-creator Christina Agapakis, who also serves as head of marketing at Ginkgo Bioworks, an enterprise finding ways and means to make biology easier to engineer. This, she believes, is not only the best way for humanity to transition away from fossil fuels, but also our best hope for adapting to an increasingly unstable planet. Adaptation doesn’t just mean building more robust flood defences or developing resilient strains of staple crops to withstand extreme fluctuations in the weather. It means building new infrastructure, processes, ethics and modes of thinking from the ground up.

Could we use synthetic biology to create a fashion industry that sends nothing to landfill, or to capture waste heat from the server centres amassing ever-increasing numbers of zeros and ones? Can we work with organic processes to create equitable supply chains that restore local craft industries with new biotechnological modes of production? The answer is yes. Absolutely. A truly radical bio-industrial revolution will see the line between pastoral farmlands, biological foundries, and industrial factories completely blurred. And in this new revolution, biology becomes both the creator and constrainer of scale, empowering everyone on the planet to live well, within planetary boundaries.

In 1997, Canadian PhD student Suzanne Simard published the findings of a study which established that plants were able to share carbon among themselves within their natural environment. The forest was able to adjust its resource production and supply chains to the mutual benefit of the collective.

The discovery of “Wood Wide Web” (living data and connections that don’t come in a neat string of zeros and ones) demanded a shift in mindset, suggesting that biologists should reconsider an evolutionary paradigm predicated on competition between and within species and, wrote scientist David Reade at the time, place more emphasis ” … on the distribution of resources within the community.”

NPOL is only just beginning its work to apply those lessons to our own supply chains, to work within planetary boundaries and to restore the fragile ecosystems on which our lives, and our economies, depend. We could do worse than to look for the forest for guidance as we seek to scale the conditions for an ecosystem of products that are alive with life.