The Future of Fashion is Skincare:

Exploring ‘Next-to-Skin’ Technology with Rosie Broadhead

In conversation with textile designer and researcher Rosie Broadhead, founder of the material innovation platform Skin Series and co-founder of Phiome, we explore how probiotic textiles are challenging our separation from nature, reframing health, and awakening the invisible intelligence of the microbiome. Skin Series is a collection of activewear made from knitted fabrics embedded with bioactive ingredients, exploring how clothing can actively support skin and body health. Phiome, meanwhile, develops microbial coating technologies—biofabricated to rebalance the skin’s microbiome and reduce unpleasant smells. In doing so, Rosie’s work reminds us that we are not one, but many.

BIOLOGICALLY-RESPONSIVE BODY LAYERS

Natsai Chieza: Can you walk us through your journey from fashion design to working with living microbes, and how that transition has influenced your perspective as a material researcher?

Rosie Broadhead: I’ve always been interested in the interaction between garment and wearer. During my undergraduate degree in fashion, I specialised in menswear, which has a strong focus on functionality, often expressed through a utilitarian aesthetic. What I liked about that was how there are all these rules—rules that are almost meant to be broken. You can fixate on things like the topstitching on a jacket or the placement of a pocket. I was pulled into that obsession with functionality and performance, and how we can create new ways to interact with our clothes. So after graduation, I went on to work for a cycling company called Rapha, which was a very eye-opening experience. I started out in 2015 as an assistant to the head of R&D. We worked on everything from aerodynamics—studying how air clings to the body depending on fabric textures—to other technologies like waterproofing and moisture-wicking. All these elements were aimed at improving athlete comfort and performance. That experience really reinforced this idea for me: that materials can directly impact how the body performs, just through what you’re wearing.

Thinking more about that connection—how the body performs, what’s already present on it—I started to question whether we really need all these added chemicals. Do we already have something on our bodies that could drive performance or improve the interaction between the wearer and the garment? That’s when I started looking into the skin microbiome specifically. At the time, I was doing a master’s course called Material Futures at Central Saint Martins, which really encouraged cross-disciplinary thinking—using your professional background as a tool to imagine alternative systems. That’s what led me to collaborate with microbiologist Dr Chris Callewaert, who’s a skin expert and has since become a long-term collaborator. That was the start of how I bridged design and microbiology.

Natsai Chieza: After that research phase at Central Saint Martins, where you began working with scientists and developing new frameworks to bridge design and science, what happened next? Which line of enquiry did you pursue?

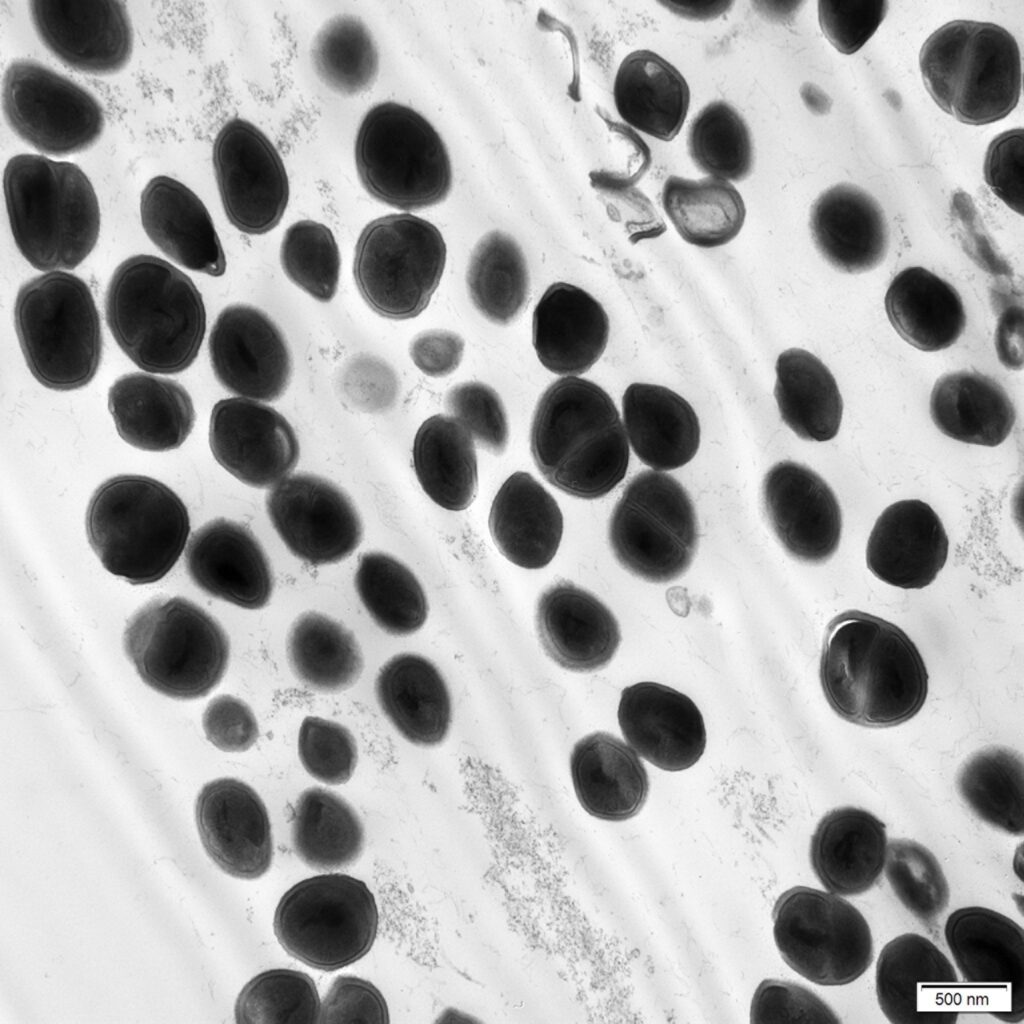

Rosie Broadhead: I became fascinated with the skin microbiome, which is this invisible living surface between the textile and the body. The phenomenon of the microbiome has possibly become more widely discussed in the last five years, yet it’s still largely unexplored. It’s a collection of millions of bacteria present on all the surfaces of our body and in the environment, and they play an important role in how our body functions, including our immune system. But there are different kinds of states of balance to a microbiome, which can sometimes transform into a dysbiosis where unhealthy bacteria become dominant, or it moves to a state of balance associated with health. A good example to conceptualise it is a probiotic [t. - 1] , like an oral supplement including Lactobacillus bacteria, that could be introduced to the gut to improve the workings of the entire digestive system. So the way that we work with our technology at Phiome—a biotech venture rethinking the future of the skin microbiome—is a similar chain reaction: trying to identify what kind of bacteria is healthy for the skin.

On that basis, Chris Callewaert and I are now branching out in our research to a textile microbiome. There is actually such a thing—it kind of mirrors the microbes on our skin, and the two can influence each other. So whichever bacteria are present on the textile, they can easily transport onto a skin and either destabilise the microbiome, or support it. What we’re doing is encapsulating enriching, native-to-skin bacteria into textiles. Once they’re transferred, they’re encouraged to grow, which can help reduce body odour and, over time, may also support the immune system and promote cell renewal.

“I'm always working on materials that you would wear next to your skin as a base layer or underwear. It’s about using ingredients found in nature—like probiotics, and algae (...) These are ingredients you’d usually associate with cosmetics, but I’m thinking about how you can actually wear them—how these garments can become an extension of your skincare.”

Natsai Chieza: And is the ‘Skin Series’ part of that same trajectory?

Rosie Broadhead: Yes, I started Skin Series while I was still working in the lab, because I really missed creating physical products. I wanted to use the research I was working on at the time to showcase its potential in a real-life application, and also to push the dialogue on how garments interact with our health.

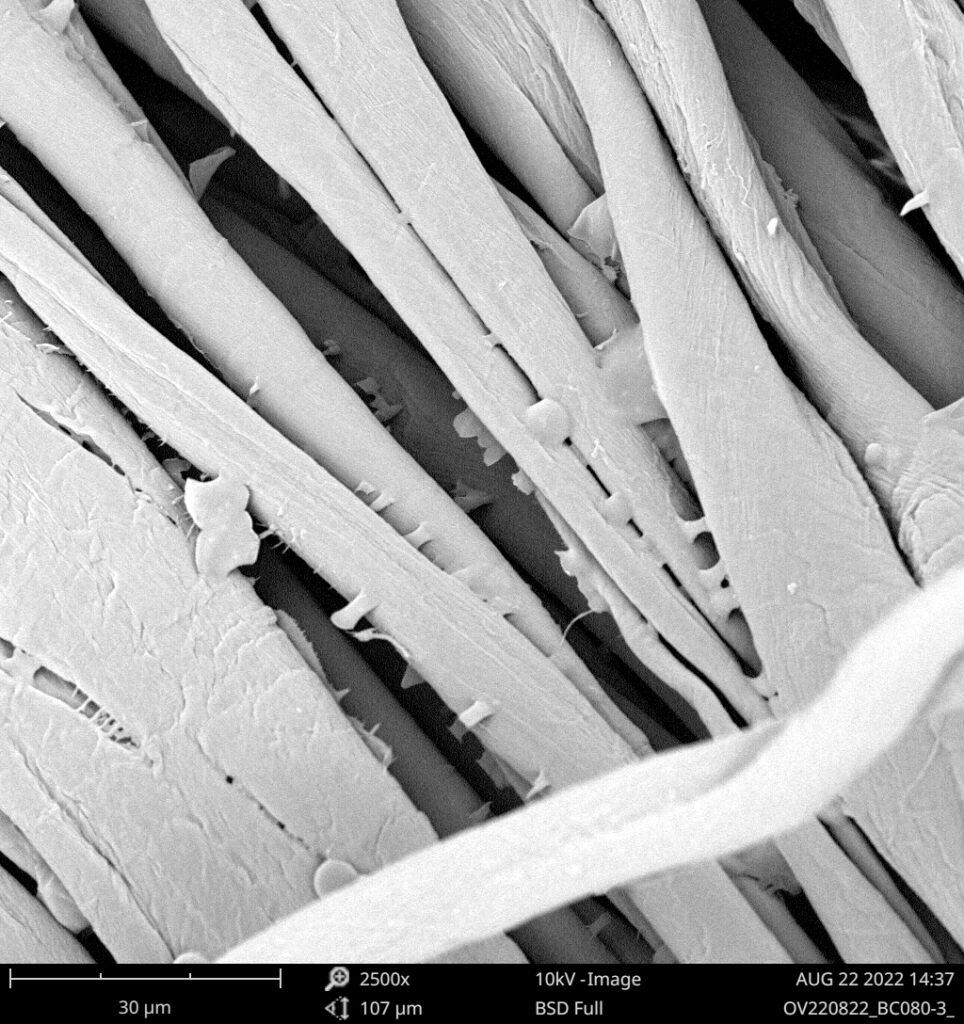

Skin Series is a material innovation platform, a brand, and a textile supplier. The research from the lab trickles into this platform, which becomes predominantly knitted materials. I’m always working on materials that you would wear next to your skin as a base layer or underwear. It’s about using ingredients found in nature, like probiotics and algae, which I’m also interested in as a skincare ingredient for textiles. I’m also exploring garments that include things like shea butter and quinoa. These are ingredients you’d usually associate with cosmetics, but I’m thinking about how you can actually wear them—how these garments can become an extension of your skincare. You might apply a skincare routine twice a day, but you could wear something like this next to your skin for 12 hours, maybe even longer.

The collection I designed comprises pieces like bodysuits, T-shirts, and vests, and then I also have the textiles available wholesale, so other designers or anyone, really, can purchase the material and make their own garments. It’s more about getting the technology out there and seeing how others choose to work with it in their own way. It is there to be accessed.

SKIN IN DIALOGUE WITH THE WORLD

Natsai Chieza: The idea of ‘next-to-skin’ as a typology is fascinating. Ultimately, the question of benefit comes down to this: what kinds of molecules are you trying to deliver to the skin, or what are you protecting the body from? It’s a bold frontier you’re opening up, with an approach shaped by performance, whether in terms of aerodynamics or the body’s own systems, like the microbiome and its interaction with sweat. It’s a compelling perspective—especially in a landscape where so many new materials are framed as ‘drop-in’ replacements, measured against existing standards. I’m curious how you navigate the design parameters that stretch across microbial, bodily, and environmental dimensions in developing these interventions.

Rosie Broadhead: The probiotic textile project I’ve been working on has been over five years in the making, so it’s definitely been a long journey. What we were doing in the lab at the beginning was quite different from how we work now. But the idea of performance has always been at the core—because ultimately, we’re trying to find new ways to replace some of the chemicals commonly used in the fashion industry, like ‘antimicrobials’ or synthetic fibres. It’s about rethinking how we relate to microbes, and how we can use that relationship to imagine new kinds of materials and performance standards.

One of the first challenges is growing the bacteria. And then, figuring out how to incorporate it into a kind of matrix that can be applied to textiles. That’s complex, because you also have to consider how the bacteria become active again—we don’t want to kill them, since they won’t function in the same way once they’re dead. Another big question is durability. In the end, it needs to function as a real product, so there are expectations around things like washability and longevity.

A key focus of Chris’ work in the lab is the odour-controlling properties of the bacteria we’re working with; a big part of our research is figuring out how to prove it’s actually doing just that. We follow ISO [t. - 2] testing standards to show, for example, that our treated textiles can absorb volatile organic compounds like ammonia or indole, which are typically associated with body odour. That comparison—treated versus untreated—is how we demonstrate real-world performance.

“The paradox of our technology is that the bacteria we incorporate into the textiles reduce the body odour as well as the need for frequent washing, yet the habit of washing clothes each time we wear them is still deeply ingrained in our society.”

Natsai Chieza: The idea of fashion becoming skincare is genuinely game-changing, though to many, it may still feel like science fiction. That brings me to the experiential side of your work and how it links to your earlier ideas around performance, not just in terms of function, but as a lived, sensory experience. What does it actually feel like to wear something biologically responsive? How does it interact with the body day to day? And why might someone choose to have this kind of material next to their skin?

Rosie Broadhead: It’s a fair question, because what we’re including are bacteria that already exist on the human body. If I’m already functioning, why would I need more of it?

I was actually talking yesterday to a cycling company where a lot of the female riders are consistently getting a vaginal thrush from wearing synthetic chamois pads. This is a prime example of a microbial shift in the negative direction, and where you would want to re-encourage the growth of healthy bacteria on your body. Most activewear incorporates antimicrobial chemicals like silver or aluminium salts on clothing to reduce body odour. On the contrary, we use a bacteria that is commonly found under our arms or in areas that we’re more likely to sweat, so that you no longer rely on these damaging chemicals.

Natsai Chieza: I love that example because it makes the application so tangible. In high-performance fields like professional cycling, there’s a clear demand for materials that meet very specific functional needs, which also makes it a useful lens for thinking about claims and regulation. How do you approach validating the effectiveness of your innovation in a way that builds trust, especially while the science is still evolving? Are the main gaps in regulation, in the science itself, or is it simply that we need better ways to communicate that this is real?

Rosie Broadhead: Storytelling has always been an easy part—broadly, I think we have already moved past this point where we find all bacteria shameful and disgusting. There’s a growing curiosity now about their potential and what they can actually do. You said earlier that it sounds like science fiction, but does it?

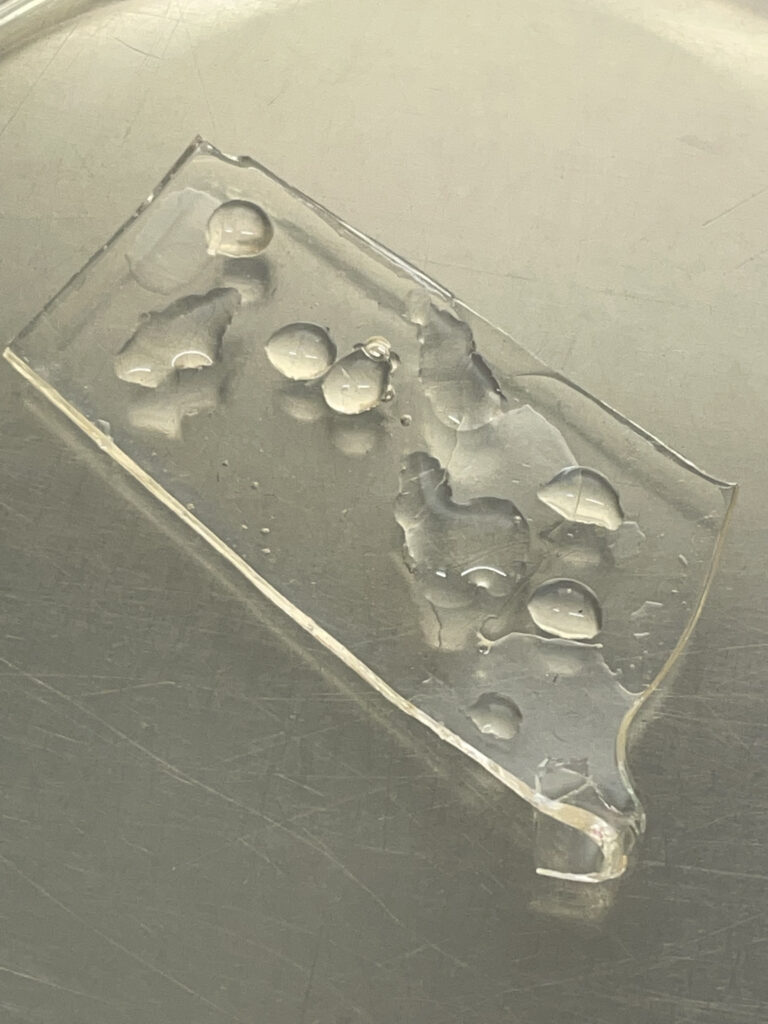

The question that I’m often asked is ‘How do I wash it? What is the wash durability of this product?’ The paradox of our technology is that the bacteria we incorporate into the textiles reduce the body odour as well as the need for frequent washing, yet the habit of washing clothes each time we wear them is still deeply ingrained in our society. Our textile treatment applied on top of existing fabrics meets the current durability standard of 30-50 washes. It remains the most challenging part of what we do, but we’ve been using bio-based methods to encapsulate the bacteria to protect them over time from water and heat. This is another challenging factor for us since we’re not creating an entirely new manufacturing system—we plug into existing infrastructures, such as a textile mill, where they are coating textiles in up to 150 degrees Celsius. So our job is to figure out how to prevent all bacteria from being killed in the first stage of the production process.

From the regulatory point of view, it can feel like we are trying to fit our technology into a system that it has never been designed for. For example, probiotics are such a novel technology that sometimes it might fall under the label of biocides [t. - 3] due to its microbiome-altering properties. Aside from that, any claims related to, for example, body odour reduction, have to be backed with ISO tests, which are standardised for antimicrobial chemicals, not actual microbes. Not to mention the price points as well, because—at least in the fashion industry—you can’t really price your product more than 10% from what it is that you’re trying to replace it with.

DESIGNERLY WAYS

Natsai Chieza: Given all those constraints—performance, price point, expectations—I imagine collaboration is crucial to navigating them. Who have you brought into this journey, and how have they helped shape the path forward?

Rosie Broadhead: Dr Chris Callewaert—a long-term collaborator and microbiologist I’ve mentioned before—brings deep expertise in the skin microbiome, while I focus on developing the textile technology. Much of this work has unfolded in a lab environment largely surrounded by gut microbiologists, which adds another layer of perspective to our approach. It’s been quite eye-opening to have that cross-pollination of intelligence, of different approaches and time expectations towards shared goals. Outside of the lab setting, we work with many collaborators, from fabric finishing to chemical companies, which are developing new innovative treatments, helping us with our own formulations. Partnering with mills is a big aspect of moving our technology out of a small, lab-scale setup to meters of textiles and working directly with brands, testing the commercial appetite for this technology. There are many moving parts.

Natsai Chieza: I suppose your superpower as a designer is being able to navigate those silos and make connections from a different perspective. It’s not just about bridging disciplines, but also bringing ideas to life in tangible ways, within real-world contexts. How are you leveraging that ‘design hat’ to really push where this innovation can go?

Rosie Broadhead: For me, it’s about understanding the fundamentals of what I am working on, developing it in the lab, and being able to position the technology within a context. If we ever want this technology to become more than what is inside the walls of a lab, how will it scale? How much heat do the production facilities use? What are the stakeholders’ expectations at each production stage? As a designer, one is actually prototyping before it becomes real, for it to be scalable. That’s more of the practical side of design.

Another aspect I’ve noticed, especially when working with researchers, is that they tend to be perfectionists. There’s always the sense that there’s a better way to do something, and to keep refining—but there rarely comes a point where someone says, ‘It’s done.’ At some stage, you just have to put it out there.

It’s also a question of how you frame it. One of my tutors from Material Futures used to use the word ‘seduce’—and I think that’s a nice way of thinking about it. How do you position something? How do you help people understand it? For example, I used my background in design to create garments that had a kind of sci-fi aesthetic or were desirable in a way that made people want to wear them. That helped move the project beyond just a little petri dish in a lab—suddenly, people could actually imagine themselves wearing it.

“We often talk about the skin as our largest organ, and it’s so open to the environment, so maybe we can rethink how we engage with it. We’re already concerned about what we eat and the air quality around us, but what about what we’re putting directly on our bodies every day? That could be another way to support skin health—rethinking the interaction between the body and textiles as something healing.”

Natsai Chieza: From that ‘designerly’ way of knowing, how do you think your ‘next-to-skin’ technology might substantially change the way that we interact with what we wear in a broader sense? What is its most exciting future potential?

Rosie Broadhead: I think there are different aspects to it. From a health and wellness perspective, this could be a vehicle for change. We often talk about the skin as our largest organ, and it’s so open to the environment—maybe we can rethink how we engage with it? We’re already concerned about what we eat and the air quality around us, but what about what we’re putting directly on our bodies every day? That could be another way to support skin health—rethinking the interaction between the body and textiles as something healing.

And then, I also like the idea of this exchange—people becoming more aware of the relationship between the microorganisms already living on our bodies and us, as human beings. It’s hard to define exactly what that means, but I think it could shift people’s attitudes, help them become more aware of what’s around them. Maybe someone realises, ‘Oh, I actually need more lactic acid-producing bacteria in my underwear because this damp chamois pad keeps giving me infections.’ Just as an example of thinking more about where different ingredients or functions are needed on the body. That’s how I see the future—not a one-size-fits-all approach, but garments or materials designed for different needs, different areas of the body, and different applications.

Cover image by Akytom Studio.