The Disobedient Curriculum:

Biodesign brings together practitioners from an incredible diversity of fields, and creating space for them to learn from each other presents a huge opportunity.

In this excerpt from Episode 06 of Ferment TV, Science in the Makingn (first broadcast Jul 9, 2020), Carole Collet, Professor in Design for Sustainable Futures at Central Saint Martins, co-director of the Living Systems Lab, discusses the emergence of the discipline and new approaches to interdisciplinary education that expands the possibilities for the thinking and making of biology with Dr Brenda Parker, a scientist and lecturer in Sustainable Bioprocess Design at the Department of Biochemical Engineering UCL, and the Co-Director of the MSc Bio-Integrated Design (Bio-ID) at the Bartlett School of Architecture and Natsai Chieza, Founder of Faber Futures.

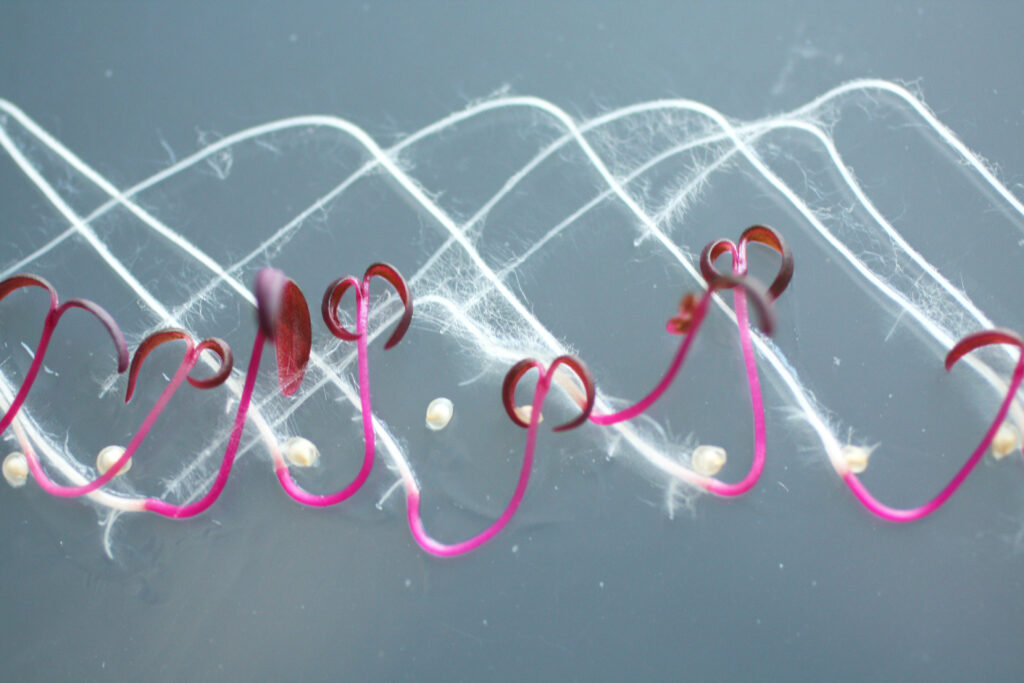

I come from textiles. This was my original training. I did my BA in Paris, but I grew up in the French countryside, in a small place but very close to nature. My father was a horticulturist and my mum was a florist. So, if I wasn’t in a greenhouse, I was in a flower shop. And so flowers and plants were everyday materials for me to play with. And then when I studied Textiles, I had deep ecological concerns when we were introduced to the technologies used to produce textiles. I felt like, “Well, hold on a second. I love creativity. I want to engage with textiles, but not if this means I will engage with an industry which is highly toxic.”

I’m trained as a biochemical engineer, so very much interested in the applied sciences. I was really fortunate in the final year of my degree to spend a year at CalTech. And I remember saying to my professor, “I don’t fit into any boxes here.” And he said, “We don’t have any boxes…” And from that moment on, I thought, well, actually, this is what I would love education to be: this place of freedom where you can deep-dive into different things and mix and match them according to your interests.

Traditionally, textiles were taught in a way where you had to choose between knit, weave and print pathways. You had to choose your craft. And I fundamentally disagree with that. I created MA Textile Futures in opposition to the traditional way of teaching Textiles. And I often talk about the “disobedient curriculum” because it was trying to do something that wasn’t following the rules.

“We felt that we needed to have a critical stance [on biodesign] and to bring more academic rigour in this fast-growing discipline.”

Biodesign and bio-integrated design are still in the “disobedient curriculum” phase. They’re new terms naming emergent fields and they don’t follow the rules. What’s the long-term hope for these disciplines do you think?

I think a lot of people still don’t know what to make of it. And even just the term “biodesign”, nobody agrees upon. There are different definitions. Brenda talks about “bio-integrated”. We talk about “biodesign”. We’ve defined it as “looking to life-conducive properties”. But biodesign is used in scientific realms in a slightly different way. But what’s important is to articulate what is truly different about integrating biology into design, whether it’s in the thinking or in the making.

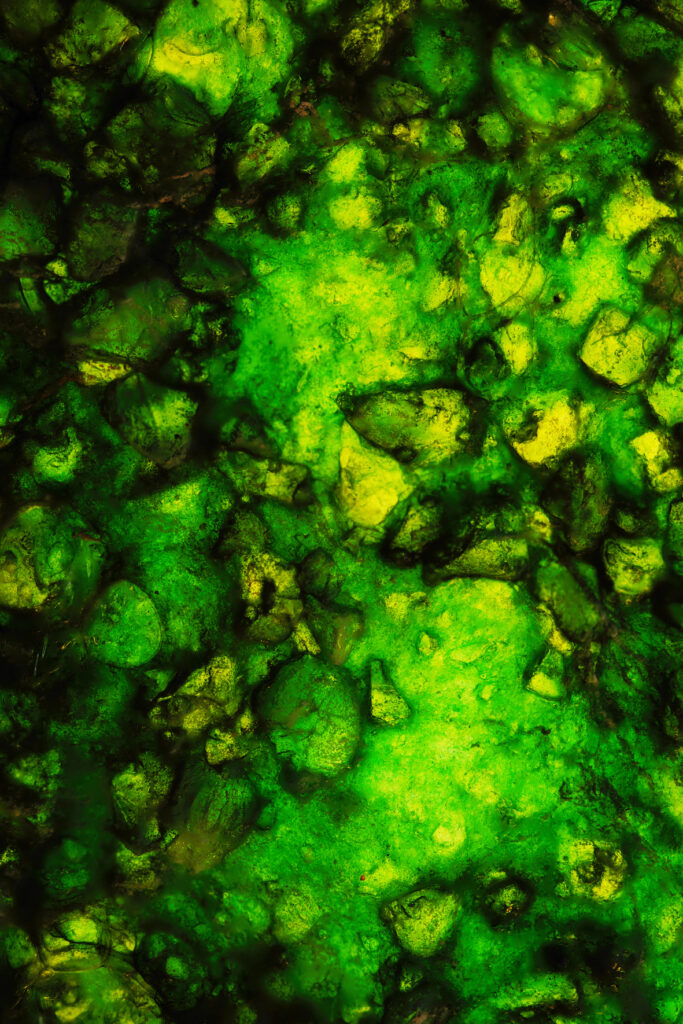

And for me, it’s about ecology and ecological systems we need to learn from. If you look at a living system, it has inherent ecological properties that we do not yet know how to replicate in our manufacturing systems. The question for me is, how does nature do it? What could we do to get a bit closer to this so that we can not just reduce our environmental impact, but actually start to regenerate it?

The past hundred years have been highly unethical in how we’ve treated our environment. And where biodesign matters most is when we use it as a means to look at this regenerative potential we have ahead of us. But when it comes to the question of what biodesign is and what qualifies as biodesign, I agree with your comment, It’s too difficult to place because it’s still a growing discipline. There are ways to framework it. There are ways to critique it. But we are developing the language as we go.

It’s funny, even the field that I come from, which is biochemical engineering, as an undergraduate degree program is only just over 20 years old. There was a paper in Nature describing the first conference of the first biochemical engineers, and they were like, “What is this everyman? He won’t be able to do anything.” And it’s just fear of the interdisciplinary. It makes people really uncomfortable. People want to know, well, what are you? Are you a scientist? Are you a designer?

But I think what we have in common is being motivated by a desire for systemic change and environmental justice. And to question some of the power structures that exist by using biology or biotechnology.

I agree. We had loads of conversations around the term “sustainability”. Is it useful? Is it overused? Is it tired? And there are times I think it’s better to talk about climate emergency or climate justice or biodiversity collapse, but there’s still sort of a restriction in the language. So, I think the term biodesign will be overused and misused, but it will have a place where it’s still the right way to talk about something.

But what’s fundamental is that if we start to use new technology, like biotechnology or biology, to sustain the same mindset of overconsumption, of celebrating obsolescence, of buying a t-shirt for a selfie and then bin it, even if it’s bio-based — it’s not going to resolve anything. So we do need a complete reset and that new way of thinking.

To watch the full panel discussion, visit ferment.tv