Returning to the Stories We Need: Emmanuel Vaughan-Lee on Spirituality, Technology, and the Living World

Part II: The spirit mind connects us

Emmanuel’s perspective on storytelling underpins his work with Emergence Magazine, a platform that explores the intersections of ecology, culture, and spirituality. I begin this line of enquiry rather naively, asking him if it was born out of a need for him to “operationalise” his worldview, and with generosity, he explains an altogether different origin story that, in hindsight, lays plain my own flawed assumptions.

Natsai Chieza: When we consider the “cultural infrastructures” that exist today to create, share, and evolve our understanding of the world, Emergence Magazine stands out as a platform actively doing just that. It seems to distill many ideas and possibilities—offering clarity amidst complexity. It feels like you’ve built a “house,” if I may use that metaphor, with various formats—magazine, podcasts, retreats—that create space for meaningful dialogue and engagement. You seem to have an established understanding of how to successfully activate such a space, reaching a thoughtful and impactful community of engaged global citizens. How did you go about creating these contexts—places that allow people to practise and connect with this understanding? Especially in today’s world, where the noise and competing narratives about what it means to live well, be spiritual, or improve our lives can feel overwhelming, how do you foster a sense of clarity and purpose?

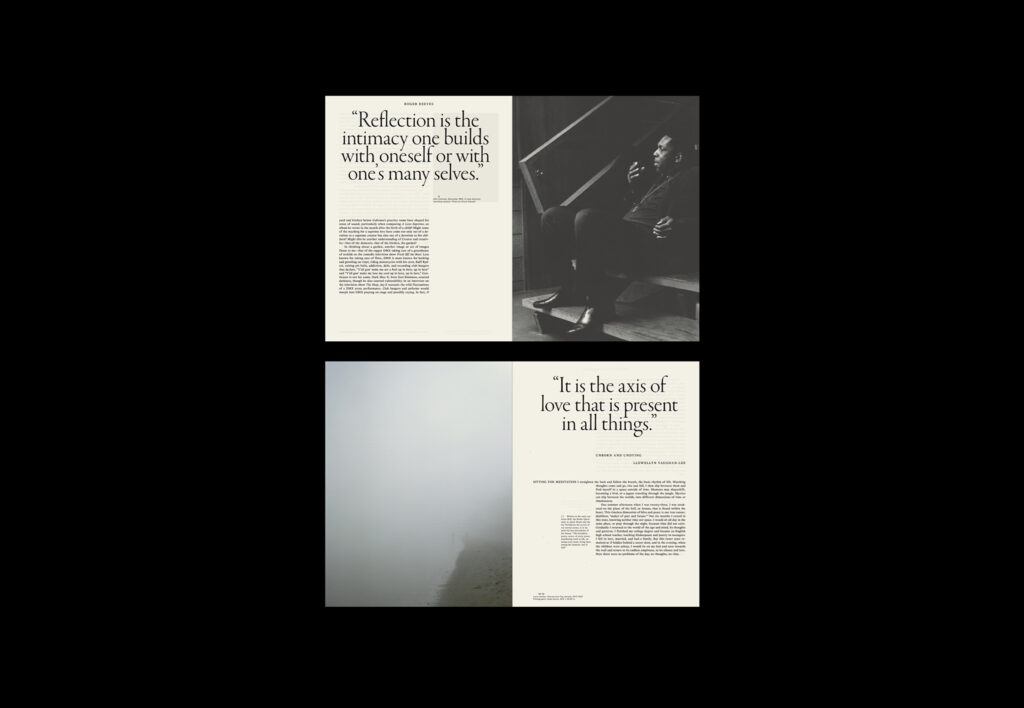

"we create a space where stories inspire reflection. If we do it right, individual agendas fall away, and something more organic and alive can emerge—something less about the self and more about connection."

Emmanuel Vaughan-Lee: Well, firstly, thank you for sharing that very kind reflection. In truth, I don’t view it as something that is purely a vision that is being manifested. The way Emergence came into being was not planned, and I’ll share the story with you.

At the time, I was working on a film, developing it into pre-production and scripting stages. My office whiteboard was filled with 3×5 cards, mapping out the structure of scenes and ideas. One day, as I looked at the board, something shifted. I saw those cards in an entirely new way—as voices representing people from different places and perspectives. Together, they seemed to point toward a way of being in relationship with the living world. It was one of those visionary moments that blur realities, something that pulls you into the imaginal realm.

My background being what it is, I take those experiences really seriously because they feel like they come from somewhere else; hence, I feel like a lot of what my life has been about is how to be ready for when those moments come, to be able to listen to them, and to not dismiss them as mere fantasy or delusion; or something that can’t be done. Because often, those momentary inspirational dumps—that’s what they feel like—often lead you away from what you were doing before or point to something you have no idea how to do. And both of those things were very true to me because I was working on a film project that I was kind of excited about. That was my idea. And here I was, given something else that was not my idea.

These moments often redirect you completely, and that’s exactly what happened. There wasn’t a booming voice saying, “This is supposed to be a magazine,” but a quiet knowing. So, I scrapped the film. I walked next door to the shared office where I worked with a team of creative people—primarily focused on our organization’s film and media projects—and told them, “We’re going to start a magazine.” None of us had any experience in publishing, but 18 months later, Emergence was born. Not knowing how to do something can sometimes be an advantage. It gave us the freedom to approach Emergence without preconceived limitations. The team had backgrounds in various artistic fields, from film to multimedia to virtual reality, but none of us were bound by traditional publishing practices. That freedom allowed us to create something unique.

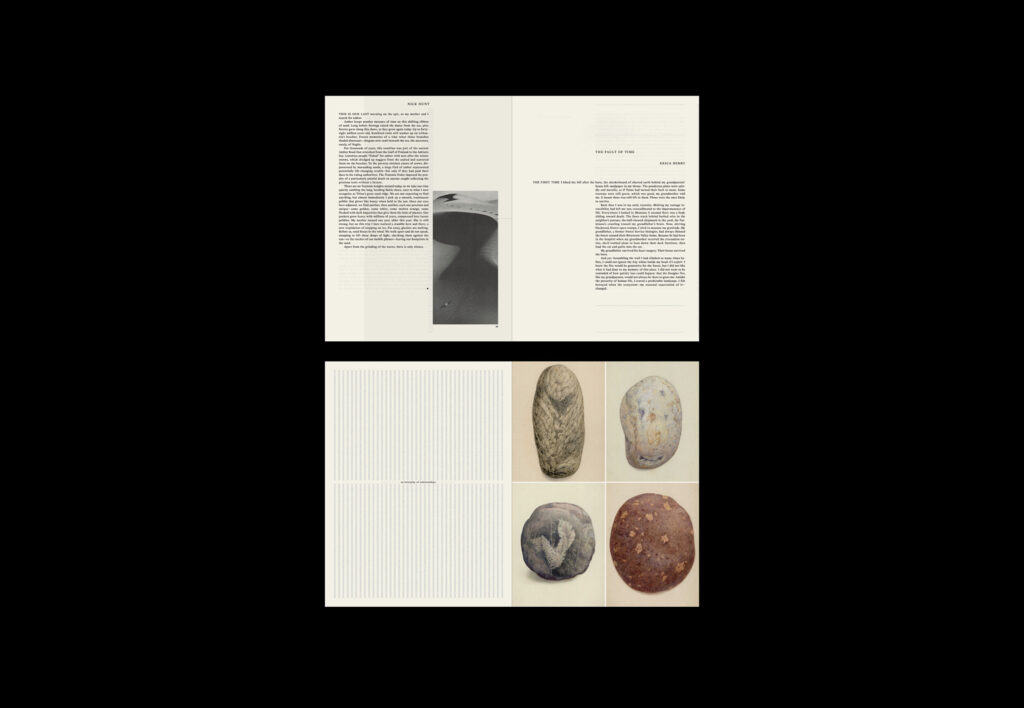

The essence of Emergence lies in the convergence of voices—each one distinct, yet all contributing to the same central thread. Some are explicit in their approach, others more implicit. Some focus on specific sectors, while others take a broader view. Together, these voices form a fabric—a foundation that doesn’t just hold something up but encases it like a blanket. It’s something you can spread out to invite others to gather or wrap around yourself for warmth. It reflects the true, multi-dimensional nature of the living world.

Stories within Emergence carry an alchemical energy. Together, they form something expansive, tapping into universal truths. When approached with care and a light touch—what I like to call “Taoist hands”—you can let the form unfold naturally, making small adjustments where needed, like moving a rock to help water flow more freely. This is how I see Emergence: not as a publishing project, but as a spiritual one.

We wanted to transcend the limits of a traditional magazine. Why tell stories in just one way when there are so many forms? Emergence became a space for stories told through text, video, multimedia, podcasts, and more—what the internet allows us to do. It’s a magazine in name only; at its core, it’s a space for diverse voices to connect, creating something richer and more dynamic than any single medium.

Our aim has never been to push an agenda. Instead, we hope to remind people of the sacred nature of creation and invite them into a space of relationship. We’re not here to tell you not to fly, eat a certain way, or vote a certain way—even when those actions are flawed. Instead, we create a space where stories inspire reflection. If we do it right, individual agendas fall away, and something more organic and alive can emerge—something less about the self and more about connection.

So that’s a very long-winded response, but it’s an honest one. And I don’t speak like that too often to people I have interviews with, but your openness and your questions are deeply moving.

Natsai Chieza: Thank you for that meaningful recounting. It means more than you realise. It might sound strange, but you’ve just articulated exactly how and why we created Normal Phenomena of Life. While the context is different, the underlying thinking and approach feel very similar. Our goal at NPOL is to tell multinodal stories about a world in which we have agency to change, viewed through many lenses—from technological innovation to craft. We aim to bring unsexy topics like supply chains to life in ways that are both accessible and deeply meaningful, weaving beauty and purpose into the narrative. At the same time, we recognise that illuminating certain kinds of stories depends on a diverse ecosystem of contributors—a diverse array of collaborators we invite into the space we are nurturing. In many ways, it’s not our space but a shared platform, an open possibility space driven only by a set of values we hold dear.

These values and our implicit dependence on nature—since designing with living systems means engaging with more-than-human collaborators—shape everything we do. They influence how we draft contracts, form partnerships, envision a commercial strategy for the products we might create and more. Storytelling expressed through various mediums and vehicles, is therefore central to weaving the relationships necessary to make this work possible.

We’ve had to learn how to frame our proposition for different audiences, and there’s been a steep learning curve, particularly when engaging with potential backers. In these discussions, the framing often shifts to something like, “We’re building an end-to-end innovation pipeline to transform supply chains with sustainable bio-based materials.” While this is accurate, or if you like “the how,” our true motivation lies in re-wiring our relationship with the living world. Unfortunately, it’s not always possible to articulate this deeper motivation or story to investors—few truly grasp that there is immense return on investment in achieving that goal or that it matters on a higher level beyond returns. Yet, it remains at the core of everything we do.

Like you, I started without knowing how to do any of this. The project emerged from a very brief conversation with our partner, who simply said, “Let’s do it!” From there, we had to figure out the “how.” This meant learning how to communicate across the interconnected relational networks that are shaping these technologies—the stakeholders of which often challenge the industrial logic embedded in so many of our dominant narratives. From building a brand, an e-commerce platform, an online journal, and even creating products from the ground up, it’s been an ever-evolving process of learning. But the common thread throughout and, perhaps, why it felt so right to have this conversation with you has been the stories—and storying we are doing through this journal—that help us strengthen our understanding and make sense of it all.

Emmanuel Vaughan-Lee: I can relate to all of that. My response to your question was the hidden one. You don’t tell funders, journalists, or even a room full of students at Stanford the whole reality. The reality is you’re also trying to craft the best thing you possibly can. You collaborate with great storytellers and artists to create a space that invites them to explore ideas they might not usually write, film, or talk about. You aim to present this work with the most thoughtful and beautiful design possible, creating a digital space that embodies the values you’re discussing—and, ideally, one that is ad-free.

It’s about leveraging technology for its strengths without becoming consumed by it. At the same time, you have to deal with practical realities. It’s not just about having a vision—it’s about manifesting that vision and working with the tools you have to create something worthwhile. Everything has to come together—design, collaboration, and execution—to create something meaningful and lasting.

Natsai Chieza: Right! Starting something you intend to “finish”—whatever that may mean—feels like committing to a never-ending rollercoaster, and so stamina and motivation are deeply intertwined in this pursuit. I often find myself discussing with others the role creatives play in shaping our technological futures: are we here to simply showcase technology, or are we meant to steer it? The OpenAI residency program offers a telling case study of an emerging backlash. When the dominant narrative for start-up founders centres on optimisation, scale, and shareholder returns—stories serving the interests of a select few—creatives risk falling into a trap. They might create something with technology that merely fetishises the substrate, in our case, Nature, without critically examining the broader systems their propositions inhabit. These systems, whether deliberately or not, are the ones we empower through creativity.

I spend considerable time thinking about how to recalibrate these narratives. How do we build a critical mass of storytellers and amplifiers who use their agency to present alternative visions? How can we create spaces that foster new possibilities, ones that challenge the status quo and open doors to more equitable, imaginative futures?

One metaphor that resonates deeply—particularly in the context of biotechnology—is the concept of “parenting technologies.” This idea aligns well with the nature of biotechnology itself: nurturing, coaxing, and sometimes redesigning living systems from scratch. Biotechnology applies human-centred sensibilities to agentic living systems, whether for pharmaceutical or climate solutions. Regardless of the discomfort this concept or hierarchy of control might provoke, the reality remains that these advancements will unfold with or without us. The key question is: In what direction do we steer these capabilities?

The notion of “parenting technologies” first emerged for me during a stakeholder engagement project called BIOSTORIES [t. - 1] , which the World Economic Forum commissioned our other organisation, Faber Futures, as part of its roadmap for synthetic biology. “I credit Drew Endy, Associate Professor of Bioengineering and Senior Fellow at Stanford, for articulating this notion of “parenting technologies” during the dialogues we initiated. He spoke extensively about shared responsibility—from the individual to collective society—and it struck a chord with me, especially as I had just become a parent myself.

Parenting technologies means grappling with trade-offs, weighing potential benefits, and embracing the constant vigilance required. There are moments of joy and inspiration, but also sleepless nights filled with unending responsibility. Your example of the Ring doorbell installed at your daughter’s house is a perfect metaphor: a seemingly small piece of technology, yet one that illustrates how we can never fully step away from what we create.

This brings me to a deeper question: How do we carry ourselves spiritually in this moment? So many of us are striving to steer these technologies toward positive outcomes. Yet, we are constantly confronted by systems that insist on maintaining an extractive relationship with the living world. How do we remain connected to what the heart knows is necessary, even when the path forward feels daunting and overwhelming?

"Our duty, then, is to protect that vision—whether it’s a story, a seed of an idea, or the life of a child. We might not see it fully flourish in our lifetime, but we must reflect back to it the truest parts of ourselves. That’s how I see it, anyway."

Emmanuel Vaughan-Lee: That’s a powerful question, and one I reflect on often because spiritual responsibility is something I wrestle with deeply. Parenting, as a metaphor, resonates strongly with this idea. To me, the essence of parenting is about nurturing and protecting the true nature of a child as they come into this world. We teach them language and other skills, but there’s also the challenge of balancing exposure to culture without letting them lose themselves in it. If we’re good parents, we help them avoid becoming just like everyone else—someone who, by the age of six, might have a phone and lose touch with the imaginal reality that comes so naturally to a child.

For a spiritually aware person, there’s an understanding that within each of us lies a unique note or thread. That individuality is what makes creation so extraordinary. Parenting, then, isn’t just about feeding, clothing, and educating a child—it’s about nurturing their unique contribution as a soul. And to do that, you have to honour and nurture your own individuality. You can’t fully reflect the purity of your child unless you’ve connected to that same purity within yourself.

Broadening this idea, it becomes clear how much protection is required—not just for our children, but for our creative and spiritual work. As you pointed out, the world can be deeply discouraging. If you have authentic inspiration as an artist, you must protect and preserve it. You need to understand its essence so it doesn’t get diluted or overtaken by competing forces. This requires constant attention—a kind of vigilance that varies for everyone, depending on their circumstances and way of life.

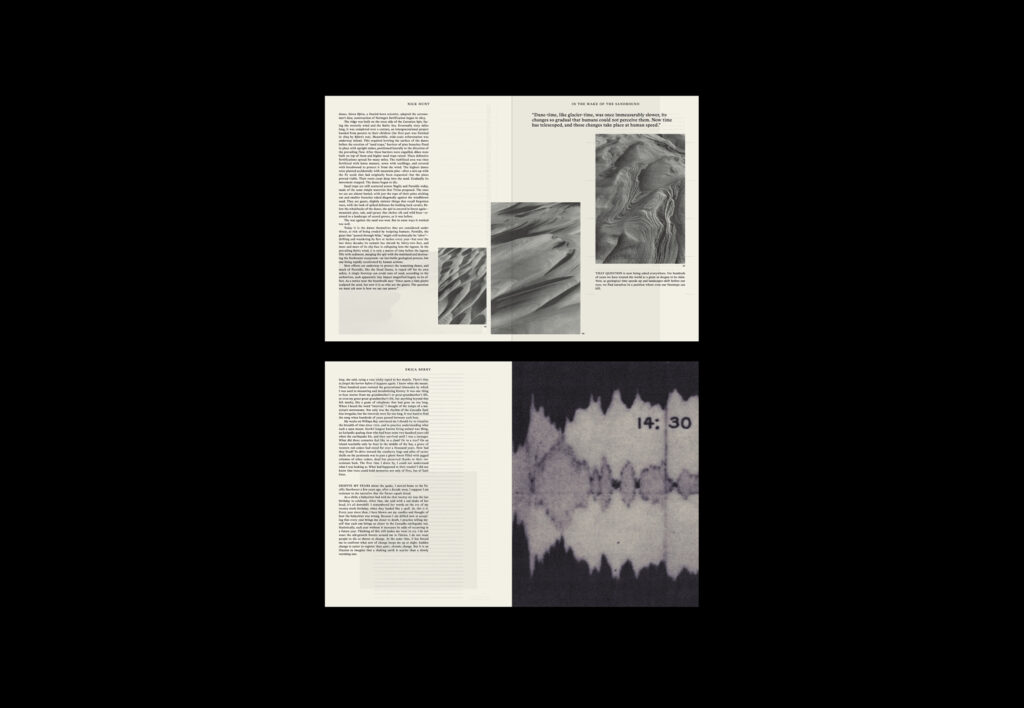

For me, living in Northern California offers a daily reminder of the greater forces at play. The redwood trees outside my home are always growing, even lifting the deck of my house. At some point, the deck will need replacing, and the house itself has a limited lifespan, but the trees will remain. They embody something far older, bigger, and longer-lasting than I am, and their presence keeps me grounded in this broader reality.

We each have our own ways of seeing and protecting what matters, but protection is essential. As a parent, you instinctively protect your child’s life over your own, and I think that same instinct applies to the future we hope to create. We may not live to see it fully realised, but we must protect it for the next generation—our children, grandchildren, and those who come after.

This approach is antithetical to the way our culture operates. We struggle to take action on something as critical as climate change because the consequences don’t feel immediate enough. Even when the evidence is undeniable, we find it difficult to act. Yet, some of us have stepped outside those narratives. We’ve embraced different stories and envisioned a different future.

Our duty, then, is to protect that vision—whether it’s a story, a seed of an idea, or the life of a child. We might not see it fully flourish in our lifetime, but we must reflect back to it the truest parts of ourselves. That’s how I see it, anyway.

As our conversation draws to a close, I ask Emmanuel how he maintains hope in the face of so much fragmentation and disconnection. His answer is both practical and profound.

“I focus on what I can protect,” he says. “The sacred doesn’t disappear; it just gets covered over. Our job is to create spaces where it can be remembered—through stories, through relationships, through care.”

Emmanuel’s reflections remind us of why stories matter—not just as entertainment or escape, but as tools for transformation. They hold the power to reconnect us to the living world, to one another, and to the sacred fabric of existence.

“Stories are containers of possibility,” he says. “They guide us home.”

Cover image: Still from the film The Nightingale’s Song.