Returning to the Stories We Need: Emmanuel Vaughan-Lee on Spirituality, Technology, and the Living World

Part I: The spirit mind guides us

THE SACRED INTERWOVEN: SPIRITUALITY AS A WAY OF BEING

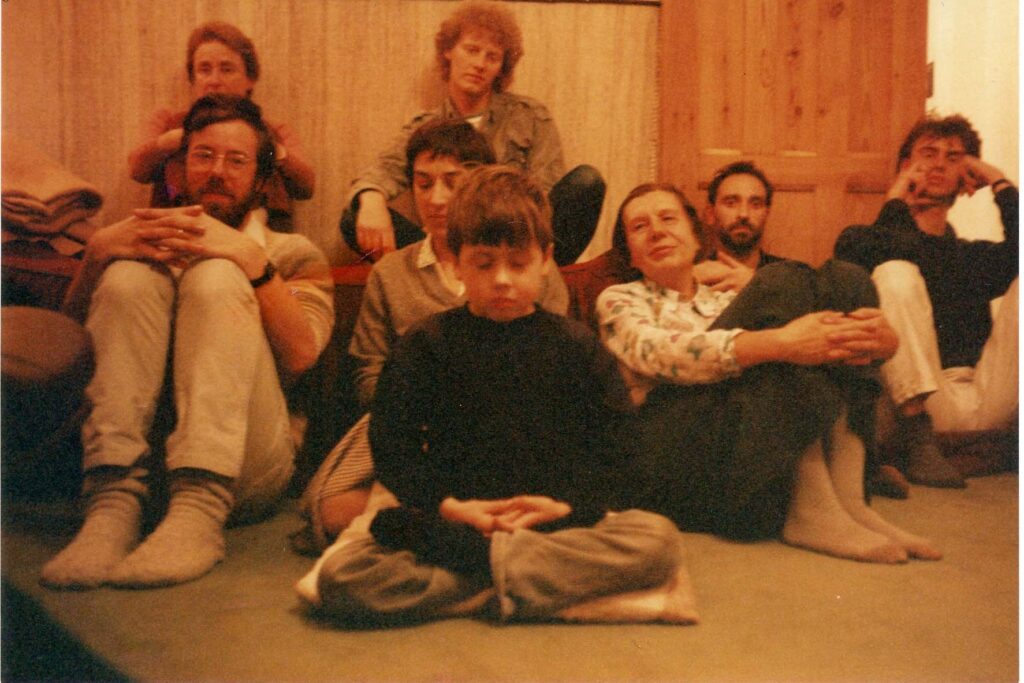

Shaped by a unique and spiritually immersive upbringing, Emmanuel’s understanding of the spirit mind is deeply personal. Born in London, he grew up in a household where the boundaries between the sacred and the everyday were seamlessly blurred. His father, Llewellyn Vaughan-Lee, a Master Sufi teacher, and his mother, Anat Vaughan-Lee, an artist and mystic, created a home that was more than a family dwelling—it was also a spiritual centre. In their North London house, spirituality was interwoven into daily life.

Emmanuel recalls how their home became a gathering place for eighty to a hundred people each day, who came to meet Irina Tweedie, a Sufi mystic who had trained in India and was living on the first floor of his family’s home during that time. “Nobody ever asked what was going on,” he reflects. “They were very polite about how a hundred people would start gathering around this nondescript residential home on a plain tree-lined street.”

For the first twelve years of his life, Emmanuel was enveloped in this reality. As Irina Tweedie neared retirement, Emmanuel’s father became her successor, and the family relocated to Marin County, Northern California, where his father established a new spiritual centre.

The move from London’s urban sprawl to the wilderness of Northern California marked a profound shift. “We moved to a tiny town called Inverness. Suddenly, the forest was my backyard. I experienced the wild in a way I never had in England, where the woods always carried the imprint of human management.”

This rootedness in the unspoiled Californian landscape planted seeds of reverence for the natural world, shaping Emmanuel’s creative pursuits and deepening his connection to the sacred—a connection that would later inform his work as a storyteller and curator.

"Spirituality—when it's become so diffused and removed from its roots—becomes a bit dangerous because it devalues something that was so profound and that underpinned the nature of existence in so many cultures for most of human history. [...] It's become like so many things in our culture: hard to really pin down what the meaning is. But that doesn't mean there isn't a real hunger for the 'other'.”

Today, spirituality, for Emmanuel Vaughan-Lee, resists easy definition. He draws on the wisdom of ancient Sufi masters and personal experience to frame it as an inherent quality of existence, one that permeates all aspects of life. Reflecting on this, he shares:

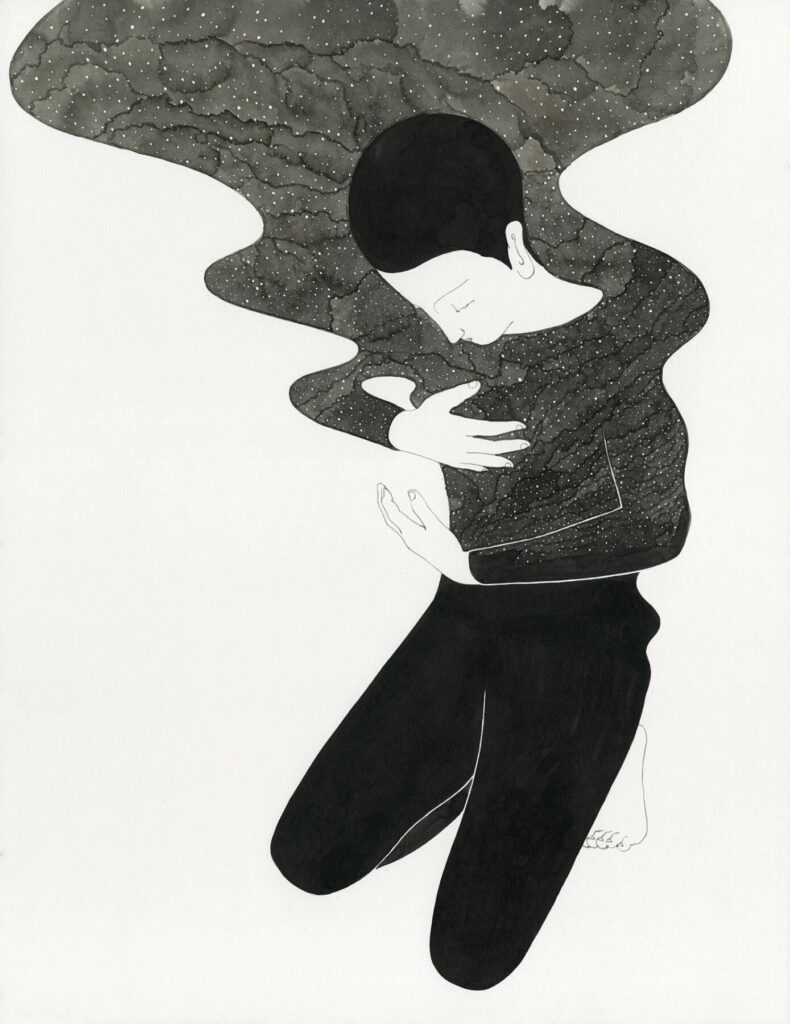

I have always loved the saying of this ancient Sufi master from the 9th century, Dhul-Nun al-Misri. He said, “Whatever you think God is, it is the opposite of that.” To me, there is a divine substance that is imbued in all of creation, and that substance is what makes water vapour move from the base of a tree to the top. But it is also what we can connect to as a substance outside of ourselves through various forms of practice or awareness that were once embedded in a culture like it was for the Tibetans or the Coast Miwok people [t. - 1] , who walked the land where I live in California for millennia, and that was what gave them an understanding that this fabric of reality was interconnected and interdependent. It was sacred because it was imbued with spirit, and that spirit was something that they were a part of. And so their whole worldview and way of being were built around that understanding because they were in relationship with the tree, and they were in relationship with the forest, just like the Tibetan Lama [t. - 2] was in relationship with the mountain top, and the plateau, and the weather. And all of those forms weren’t very different in some respects from the prayers that were offering homage to an aspect of that divine reality and spiritual way of being. So, for me, spirituality—when it’s become so diffused and removed from its roots—becomes a bit dangerous because it devalues something that was so profound and that underpinned the nature of existence in so many cultures for most of human history, really. Instead, it has been replaced with an understanding that this “something” is more about us than anything else, even though we claim it’s about that “other.” A spiritual way of being that makes you feel better about yourself, or is slapped on a wellness retreat description, or is part of the reason you might want to have a vegan banana smoothie. It’s become like so many things in our culture: hard to really pin down what the meaning is. But that doesn’t mean there isn’t a real hunger for the “other.”

STORY IS TECHNOLOGY

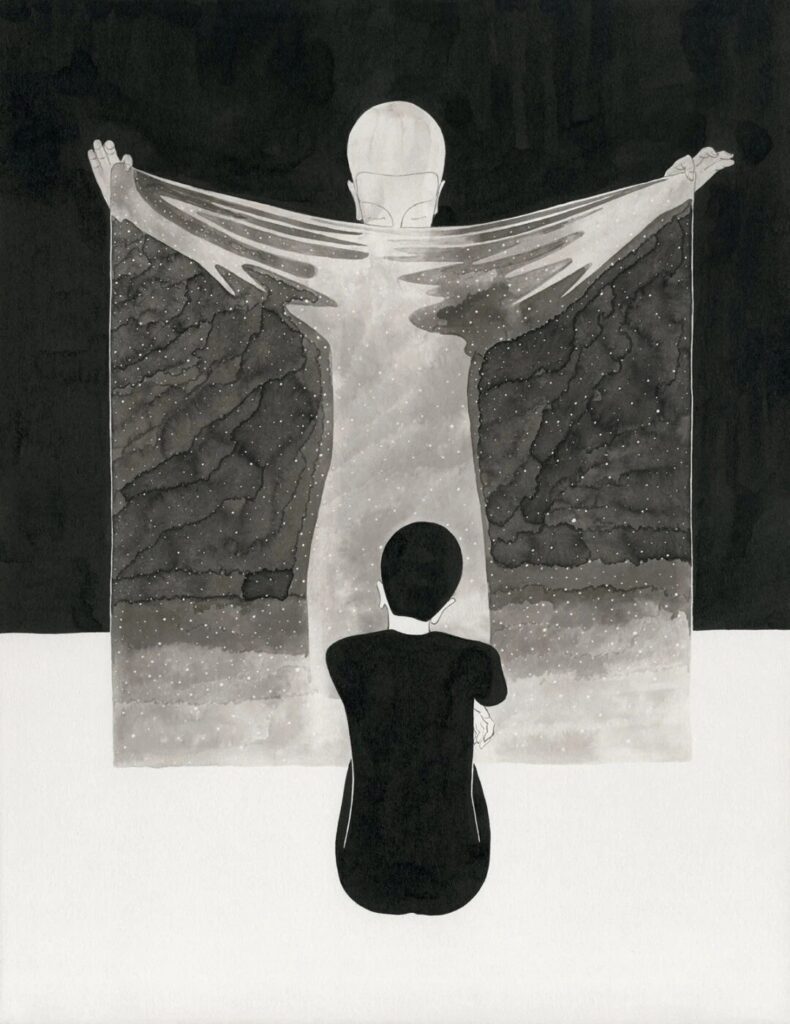

In a world shaped by industrial systems and technology, it’s easy to lose sight of our deeper connections to the living world. I talk to Emmanuel about how embodied scientific practices in the field of biology reveal cycles and interdependencies that challenge how we usually think about productivity and care. How these insights almost force a shift in how we see and live, moving beyond technology to embrace more relational and meaningful ways of being. And how we take seriously the notion of storytelling is a vital interface to explore, understand and share these connections. I tell Emmanuel that I am deeply interested in how he has pursued storytelling to give language and form to what, in a secular society, may feel like the most remote, almost unknowable parts of our being. Emmanuel sees stories as vessels for both practical knowledge and metaphysical truths. Drawing from ancient myths, he emphasises their dual role: to provide guidance and evoke awe.

"[...] A good story should always point you towards the nature of something or the experience of something versus naming it outright. Because when you name it outright, you're told. But if you're oriented towards something, you're invited into that space, and you discover it for yourself."

Spoken words by Emmanuel Vaughan-Lee

There are many different kinds of storytelling. Take Tyson Yunkaporta, for example, the Aboriginal writer and scholar who I recently interviewed for our podcast, whose book Right Story, Wrong Story [t. - 3] explores how many stories are “wrong.” These are the stories used for propaganda, bigotry, hatred, and colonisation, perpetuating myths that keep people in power. For the most part, these are the stories that still run our world. You can see it playing out in my country right now as we approach the election. I walk down the high street in London and see those stories everywhere—embedded in brands and in all the ways a very strange reality has become normalised.

This reality is based on a capitalist model that disregards the well-being of the planet and its people. It is bent on destroying itself in pursuit of a completely false myth. Ancient myths, after all, were stories. Stories are tools—humanity’s most potent technology. More powerful than the wheel, and older too, we’ve been telling stories since the very beginning, using them to understand how to live in relationship with the world around us and with each other. They were told to help us process the grandeur of natural forces, like what a storm could do to a coastline or how a tsunami might wash away an entire village. A tsunami became a story, and that story served as a warning. But it wasn’t just an instruction manual—it was imbued with emotion and meaning. It captured a whole landscape of understanding. Stories like these helped societies bring forth values and establish the principles that would define their civilisation, whether it was the size of a village or a city like London.

To reshape how we relate to the living world and embrace the values that relationship demands, we need to break free from the dominant narratives that shape our lives. We cannot remain passive consumers of these stories; we must step outside them. If we don’t, we risk unconsciously living by their rules, unable to question them or see alternatives.

The “right” stories, however, bring us into the right relationship with the world. These stories are plentiful; they are the ones that have been told for millennia. What’s remarkable is the diversity of these stories—each one deeply rooted in the place and the people who told it, shaped by their specific journeys and experiences. Yet, despite their diversity, they all point to the same fundamental truth: that there is an “other,” something greater, and we are a part of it. These stories teach us how to relate with that “other” and to respect it for what it is.

Stories that help us reconnect with the living world are not new; they are ancient stories retold for our current time. But we have become so distant from the foundational truths of existence that we must name and explain them in ways that can feel reductive. It’s a reflection of how far removed we are from the fabric of existence that these stories once illuminated so naturally.

[…] A good story should always point you towards the nature of something or the experience of something versus naming it outright. Because when you name it outright, you’re told. But if you’re oriented towards something, you’re invited into that space, and you discover it for yourself. Wrong stories tell us things, and they use fear to harness the power of those emotions to achieve a certain goal. But if you’re invited into a space, and that space itself is not something that is trying to coerce you or manipulate you—but it actually is trying to remind you of something that already exists, that’s very ancient, dormant or latent inside of you—then the alchemical nature of that story begins to work in a different way. Just like if you have a conversation with somebody, and that person is trying to prove something to you and hammering that point home, you are going to put up resistance because you’re being forced into it. But if you’re invited into a participatory exchange, everything shifts, and the nature of your being can be more open and receptive. That’s what fascinates me about stories. We tell so many stories all the time, and we do it mostly unconscious of how they work. And, of course, the master storytellers and the people behind the advertising campaigns that try to tell us what to do with our life, they understand this. Some of them more directly than others. But if we’re going to find a way out of this world we’ve created for ourselves—one that has also been shaped for us by certain forces—stories will have to play a central role. They have the power to contain us as we attempt to return to these core ways of seeing the world and hold onto them, even while facing the relentless onslaught of a world that refuses to give up these ways of being. A world that prioritises profit and personal gain over any form of relationship that honours life.

COLLIDING FORCES: TECHNOLOGY, THE MARKET AND SPIRITUALITY

We are living in a time where technological mediums are rapidly disintegrating our sense of shared realities and shared truths. With his proximity to Silicon Valley—a hub where science, technology, and market forces intersect—Emmanuel has witnessed both the promise and peril of our technological age and shares his perspectives.

“I am less and less drawn to technology than I used to be,” he admits. “I’m embracing my ludditeness with vigour and encouraging it to have its way with me for lots of reasons.” While acknowledging the revolutionary potential of innovations like the internet and personal computing, he critiques the ways these technologies have been co-opted, turning tools of openness into “a network of walled silos dominated by corporate elites and billionaires.”

One story Emmanuel shares highlights the pervasive and insidious nature of AI in daily life. Recently, he installed a video doorbell for his daughter—a seemingly mundane act that sparked a cascade of reflection. “I set it up, installed the app on my phone, and there’s an enhanced AI feature built into the program,” he explains. “It tracks motion settings to help you feel safer. But it’s also training itself—who comes to the door, who’s a good person, who’s a bad person.”

What troubles Vaughan-Lee isn’t just the feature itself but how seamlessly it integrates into the experience without question or pause. “It wasn’t really a choice; it was just built in. It’s so pervasive and under the guise of being helpful. But it’s also very dangerous—who has that information?”

This incident encapsulates his broader concerns about AI’s rapid adoption and its environmental costs. “I find AI scary. And just one of the reasons, it is the amount of power consumption that is required,” he says. “This year alone, gains made in energy efficiency have been mitigated by AI. Large players in tech are abandoning sustainability goals or turning to nuclear power to meet these demands.”

For Emmanuel, these developments are happening too quickly, with little debate or regulation. “Even though they say there are debates, there really aren’t many. It’s just being implemented everywhere.”

Navigating the Sacred in a Tech-Augmented World

Emmanuel sees the encroachment of AI and other technologies as symptomatic of a larger disconnection from the sacred. “We’ve become disconnected from the most fundamental ways of interacting with the world around us as human beings,” he says. The seductive power of technological convenience, what he calls its “miasma,” obscures our deeper connections to existence.

“I’m deeply fearful of a world where writers aren’t able to write in the way they could, because ChatGPT has suddenly changed everything,” he confesses. “And what’s real? Is there time in this world for an original thought anymore?”

Countering this disconnection requires a commitment to rituals, attention, and creating spaces that foster relationships with the sacred. “It’s always been a lot of work to stay aligned and connected to the sacred nature of existence that’s present in the living world,” he explains.”It takes a whole culture with its rules and traditions to support that way of being, to make that cycle spin.”

“I’m interested in technology up to a point, but I’m looking more and more into the smaller scale.”

“If you asked me this question five years ago, I might have given you a very different answer,” he reflects. And when it comes to stories, the real concern is not about political debates or misinformation but what he calls “the deeper falsity of existence itself.” Despite this, he still believes in the power of technology to disseminate meaningful stories, though he questions the metrics we use to measure its impact. “Is it more valuable that a thousand people read a story in a day versus a hundred people?” he asks. “The most important thing is bringing a person into a space in a way that supports that opening.”

Emmanuel argues that the most transformative experiences of storytelling happen in physical spaces—where the exchange is intimate and immersive. While he recognises the value of large-scale media, he sees a diminishing ability for digital platforms to create those same profound connections. “I’m interested in technology up to a point, but I’m looking more and more into the smaller scale.”

As Emmanuel reconciles his spiritual convictions with the demands of modern life, his reflections offer a call to recalibrate our relationship with technology. Rather than rejecting it outright, he advocates for thoughtful engagement—leveraging its power without losing sight of its limitations.

His vision of storytelling as an alchemical vessel for connection underscores his belief in the importance of human relationships and shared experiences. By fostering spaces that nurture these connections, Emmanuel hopes to counterbalance the noise of technological acceleration with the quiet clarity of the sacred.

“It’s a lot of work,” he says, “but it’s worth it. The living world and the mysteries behind it have always required our attention—and they still do.”

Cover image: Poisoned Beauty, by Gheorghe Popa.