Fungal Futures:

Rewiring How We Think, Make, and Live

Sophia Wang on bridging culture and science to unlock the biomaterials revolution.

Sophia Wang’s journey to co-founding the biomaterials company MycoWorks is rooted in a life shaped equally by poetic form, experimental dance, and molecular biology. Raised in New York and New Jersey, she was immersed in the cultural energy of the city—museums, opera, ballet—while growing up exposed to scientific lab environments through the career paths of her parents, both research scientists in biology. This dual exposure laid the groundwork for a worldview where scientific inquiry and artistic exploration were never far apart.

Drawn to storytelling as a mode of world-making, Wang moved to California to pursue a PhD in literature with a focus on oral epics. She became fascinated by how cultures name their values—who they choose as heroes or villains, what themes define their civilisational imagination. Her scholarship spanned classical Greek and Old English texts. Still, over time, she turned toward contemporary American poets—especially women like Bernadette Mayer [t. - 1] , who radically expanded the scope of what an epic could be. In Mayer’s work, Wang recognised a voice grounded in female experience and form-breaking language, which helped her reorient her intellectual practice.

It was also in California that Wang turned to dance—first ballet, then experimental contemporary movement—as a physical counterbalance to the intellectual labour of academia. This embodied practice became central to her life, opening up new pathways into the Bay Area’s art community, where she co-founded a dance company that still exists today. It was within this creative ecosystem that she met Phil Ross [t. - 2]

in 2007, assisting him on the exhibition BioTechnique at Yerba Buena Center for the Arts—a little-documented but visionary show tracing the intersections of art and biotechnology, from fermentation cultures to the first museum display of lab-grown muscle tissue by Oron Catts [t. - 3] . For Wang, this project activated a convergence of worlds that had always defined her: lab and gallery, performance and microbe.

"Wang’s work reminds us that to build new material realities, we must first reimagine the cultural myths that hold the world together."

After BioTechnique, Ross and Wang pursued separate paths—he filed patents and began exhibiting mycelium-based work more widely; she finished her dissertation while continuing to dance and perform. Five years later, Ross returned with a proposition: global companies were knocking on his door, curious about integrating his mycelium material into their products. To respond, they would need to become a company themselves. For Wang, it was the inflection point—rather than becoming an adjunct professor, she began shaping the foundations of what would become MycoWorks.

The early years were precarious. Wang kept her artistic and writing practices alive while supporting the business through performance gigs. She was, in her words, “paying for my biotechnology dreams with my dance gigs.” But with the arrival of CEO Matt Scullin and the team’s participation in the IndieBio accelerator [t. - 4] , things began to shift. For Wang and Ross, entering this high-stakes science and venture world as artists and academics was disorienting—they wondered aloud if any other founders were philosophers. But they also realised that their fluency in producing artworks and performances, their grounding in cultural storytelling, was a distinct advantage.

Today, MycoWorks is 300 people strong. And at its core is Wang’s conviction that culture shapes the way materials are understood, adopted, and valued. The company’s success has been underwritten by a deep narrative capacity—something many tech founders overlook. MycoWorks doesn’t just grow mycelium; it tells stories through matter. Wang’s work reminds us that to build new material realities, we must first reimagine the cultural myths that hold the world together.

CULTURE MAKES TECHNOLOGY

Natsai Chieza: I remember one of the more affirming pieces of feedback I received before graduating from architecture school. It came from our lead tutor—one of only two women in an otherwise deeply male-dominated faculty. She told me that I was good at my craft, that I was a powerful storyteller, and not to take that for granted. Because it meant I was a good salesperson. I stood there, slightly bewildered, already certain I was leaving the discipline. She added that this is what architects do: they tell stories to seemingly disparate stakeholders in order to build.

That moment has stayed with me. And I think about it often—the stories we tell ourselves and each other about what’s possible, and how storytelling can be a powerful tool, for better or worse. Yet even now, the ability to tell a compelling story remains an undervalued skill, despite being the very thing that gives ideas shape, meaning, and momentum.

Why I wanted to talk to you is because as an artist-founder you embody that paradigm so clearly, and the fact that it’s woven into Mycoworks’ DNA speaks to the confidence with which you felt you could hold space for that in a place that trends towards having singular narratives about the utility of technology.

Sophia Wang: One of the moments I was proud of at IndieBio was when we were practicing for our pitch day. It’s a common practice where you do three months of work, and then you have to present your ideas to the public. Everyone had finished their round, and then the main facilitator said, ‘Sophia practised, she rehearsed,’ And I was like, ‘Yes, that is my theatre and performance background.’ Coming to the front like you actually have to rehearse with your body in a space, because you are on stage, and it’s not just your deck. It’s actually your presence that matters, because you are selling by way of it.

Natsai Chieza: Compelling stories rely on precise language—it’s what allows them to carry meaning that resonates beyond boundaries. Your title at Mycoworks is Chief of Culture, which is intriguing on many levels. Can you tell me a bit about what that means?

Sophia Wang: Yeah, absolutely! First, I’m fully aware of the pun in ‘Chief of Culture’—especially in a fermentation-based space—but the title was a way to capture my role in the company. My job is about ensuring that our entire system aligns with the values we want to uphold at every touchpoint. Culture—broadly defined—is how we relate to one another, how we behave, and what we practice as a community. Within MycoWorks, it’s exactly that. As a co-founder, I helped shape the company’s vision, mission, and values—the foundation of its identity. From there, my focus is on how we live those values every day, whether in collaboration, problem-solving, or the partnerships and stories we choose to share with the world. Ensuring that alignment is something I care deeply about.

When people ask me what my passion is, I could say many things—dancing, writing, working with mycelium. But when we were at Asilomar [t. - 5] , someone asked me, and I found myself answering: justice in all its forms—ecological, economic, social. I see MycoWorks as a kind of community space where we observe the right values and respect the rights of all entities involved—people, mycelium, and the ecosystem—so that everything can thrive in a way that is both generative and just. That’s why I valued the conversations that took place at Asilomar—especially the debate around the anthropomorphised rights of nature versus human rights. I think about those tensions constantly in our approach to technology. As our work with mycelium has scaled from bench-top cultivation to mass production, the underlying principle remains the same: enabling it to self-organise, flourish, and regenerate. We act as stewards, guiding its growth through the cultivation knowledge and techniques we’ve developed, which form the foundation of our Fine Mycelium TM technology—our distinct way of working with it.

"I approach my work in culture as a way of modelling a better world within the existing one. We’re not just imagining a different way of working—we’re actually doing it. And if we can do it here, it means others can take these practices into their own communities and spaces. That’s how change happens."

At the same time, we need to practise these principles collectively—as the people doing the work. That’s why our core values are expressed as: Be mycelial, which encourages connection and collaboration to drive innovation. Cultivate quality, which means striving for the highest standards. And Grow the future, which is about building today in service of generations to come. As a team, we try to embody the qualities of mycelium itself, growing organically, balancing resources, needs, and responsibilities. We operate as an interconnected whole, cultivating quality not just in the materials we make but in how we relate to one another. We’re creating a beautiful, high-quality, desirable product, and that same standard should apply to the way we work together. Mutual respect is fundamental. When things get intense—problems arise, deadlines tighten, stakes are high—it’s what allows us to harness everyone’s contributions productively.

And finally, there’s the future. Our technology is forward-looking, yet grounded in history. It draws on long-standing traditions while proposing new ways to think about and create materials. But it’s not just about advancing science—it’s also about cultivating the people who will carry it forward. So I think a lot about how we’re growing the next generation of leaders and innovators within our own walls. No one has built a factory to produce mycelium at scale before. We’re all learning together, solving challenges as they come. That process is incredibly energising for the engineers and scientists who’ve joined us. It’s also why we’re a learning-focused company. We have to be.

For me, all of this work is deeply connected to my passion for justice. I see this company as a platform for justice in many forms, and what we’re doing here is portable. The values we’ve set—aligned to our business needs—are also fundamental principles that can extend beyond MycoWorks into community spaces and social initiatives. They’re universal. I approach my work in culture as a way of modelling a better world within the existing one. We’re not just imagining a different way of working—we’re actually doing it. And if we can do it here, it means others can take these practices into their own communities and spaces. That’s how change happens.

IN THEORY AND IN PRACTICE

Natsai Chieza: I think a lot of founders consider how to operationalise their mission, vision and culture into the DNA of the company, but struggle with what that looks like in practice. Like, how does this show up in someone’s work contract? Or—and this may sound a little clinical—how do you approach progress reviews? What shape does progress take in this context?’ There’s a real question around the practicalities of embedding these values within company culture in a way that isn’t dependent on any single individual. I’m really curious about how you have addressed that.

Sophia Wang: It’s a constant and fascinating tension. I never lose sight of the fact that we are a venture-backed startup, operating on a very specific path with clear revenue targets and financial commitments to the investors who have made this possible. So, I think it starts with being incredibly honest about our constraints and business needs. We are all here because we believe in this mission—it carries deep meaning if you want to engage with it on that level—but at the same time, we are practically running a business. Engaging with us means engaging with that reality.

I can be idealistic about the metaphor of what we’re building as a community, but I also fully recognise the practical side: we are an employer, responsible for supporting our team, ensuring they feel inspired and successful, and driving the mission forward. That’s why I find performance reviews such an interesting question. They serve as a real touchpoint for values and mission—a moment to ask, ‘Why are we here? Why are you here? And why are we doing this together?’ If we can be radically honest about that, it creates a foundation for meaningful conversations. And sometimes, the answer is purely pragmatic: ‘I’m here because I need a paycheck, and that’s why I need a raise.’ Or, ‘I believe in the mission, but I also have financial realities to meet.’ I welcome that level of honesty. Once you’re completely real about why we’re here, then you can have an honest conversation about the terms of engagement and agreements.

One of our biggest areas of focus is seeing feedback as a gift—and practising how to receive it, even when it’s challenging. Because ultimately, that’s how we reach the best solutions, how we grow, and how we flourish. It’s also an exercise in human nature and social conditioning—what people feel able or unable to say, what they’re comfortable owning, and how their personal histories show up in the workspace. Work is porous. How we handle correction, failure, and even discomfort is deeply shaped by who we are. But rather than alienation, we’re aiming for engagement, creating an environment that is both ethically grounded and practically clear about why we’re here. At the end of the day, it’s a choice to be here. MycoWorks offers a particular kind of environment—one with unique challenges but also real inspiration. Of course, choice exists within the constraints of capitalist wage labour, where different people have different levels of access and opportunity. But fundamentally, this is how I think about progress and performance: We are in a contract with one another to make this thing happen. You are here because you want to be and need to be. And we want you here and need you here. And so, together, we figure out how to make it work.

Natsai Chieza: It’s easy to take all of this for granted. Often, the assumption is that hiring for the right “culture fit” means people and therefore the company, behave a certain way. But culture doesn’t just happen. It has to be intentionally shaped. And so, much of how we talk about this and signal this can feel performative, internally and externally.

Sophia Wang: Yeah, it’s a fascinating balance between performance and authenticity, isn’t it? I’ve been diving into theatre theory lately, just for my own personal practice, exploring the real yet unreal nature of the stage. What happens within a theatre space, or during a performance, is a unique tension point for me. As a leader, you do need to manifest the future, to talk about what’s to come. But you must do so with authenticity—to where you are today, and who you are as a company and as a person. There has to be a thread of truth running through all of it, even while you’re envisioning possibilities ten years ahead.

I’m sure Buckminster Fuller’s [t. - 6] work has probably come up for you, as it has for us—he’s a touchstone for this technology. What might seem fantastical, like chasing dreams, is often how you reach a new horizon. It might not look exactly like the initial pitch, but it’s part of the continuous path forward. […] Did you hear about the new republishing of the Archigram Archive [t. - 7] ?

Natsai Chieza: No, I hadn’t.

Sophia Wang: I spotted it on Instagram—we have to hunt it down! Before I connected with Phil, I was trying to get my bearings, looking for internships that might help me break into the art world. One of the first ones I did was at the Exploratorium [t. - 8] . I got assigned this research project on speculative architectures, and that’s when I discovered Archigram. It completely blew my mind. I’ve always loved that whole era—music, design, fashion—but I’d never come across Archigram before. It was such a revelation.

Natsai Chieza: I really love that you bring Fuller and Archigram up. Alongside the Case Study House programme [t. - 9] , they are all North Stars whose philosophies have provided touchpoints for me in thinking about how we design with living systems. What these movements did so well was to reveal architecture as the ultimate proposition space. Not fixed, not polished—but iterative, open-ended, pushing extremities and built fundamentally to ask questions.

That mindset feels so relevant to biotech right now. Because what we’re seeing is a tendency to map familiar systems—industrial, economic, even aesthetic—onto biology. And biology just doesn’t work like that. So we have to ask: how do we prototype with it in a way that honours its logic, rather than trying to control or abstract it?

That’s where these movements feel so instructive—they weren’t trying to scale immediately. They built ideas in the world. And it’s ok if some of these ideas fail, because failure teaches something more fundamental. I think we need more of that: full-scale, real-world experimentation that gives form to alternative futures. But the systems we operate within—particularly markets—aren’t really set up for that. They’re risk-averse. They need proof before possibility.

Sophia Wang: And if that’s your only frame, you never get to do anything truly new.

Natsai Chieza: Exactly! Which is why I am curious to hear from you about how you’ve melded these worlds. Mycoworks feels like one of the few examples where that tension has been negotiated so fluently—where material innovation and commercialisation haven’t come at the expense of culture, or story, or values. You’ve made room for both. That feels rare. And necessary.

Sophia Wang: There were tensions throughout the process, right? We definitely had a moment in the early days of the company where we cycled through teams. People who started with us couldn’t continue on the full journey. In a way, Phil is one of those people—he’s doing Open Fung [t. - 10] now, not actively working in the company. He got it going, but then realised he needed to work in a different way.

There was a shift in the company where some people started asking, ‘But are we doing art?’ We began as an art practice, and that remains fundamental to what we do. Those art objects and design experiments showed what was possible, but now we are directing that possibility towards creating scalable technology with practical applications for products that can be sold to consumers.

It made sense to me because, to realise the full range of possibilities, you need something real and tangible that delivers value to the people who are developing it, and then delivers value back to you. Existentially, it was a difficult moment, especially for Phil, because this was his art practice turned into technology that was handed over in a tech transfer to the company. What had been his art studio became MycoWorks. It was a form of colonisation.

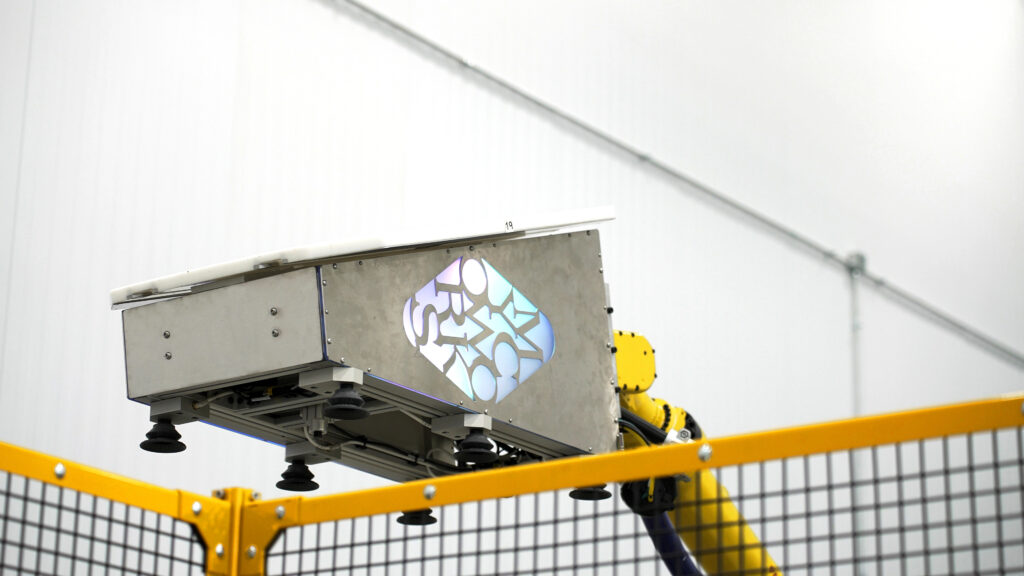

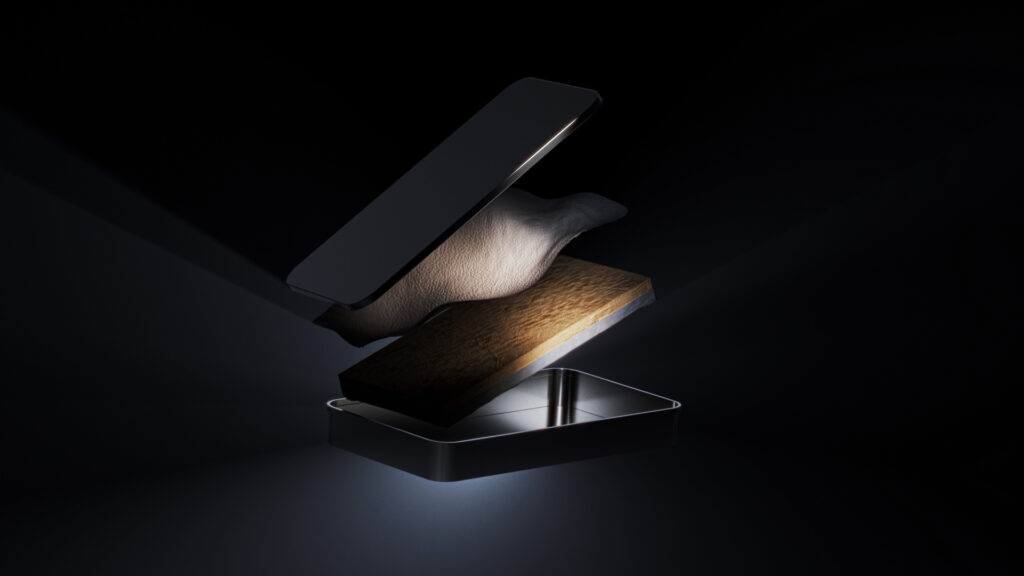

My art practice has always been separate from the company. Sometimes it serves the company, and other times, the company serves my art. I made this amazing renegade dance film in our factory before it was even built. One weekend, I snuck in when the floor was empty, shot it in eight hours with my crew, and then we were out. There are moments like that where the worlds intersect, but I’ve been able to compartmentalise my work, separating what serves the company and the technology, which ultimately became focused on a singular product: Reishi. This product is based on a clear, defined technological platform called Fine Mycelium TM, which we developed through the process we learned from Phil.

Beyond that, we have an incredibly creative brand and marketing team led by Xevi Gallego, our Vice President of Brand and Marketing, who is also an artist. I think he truly understands the power of the stories we can tell through this product, mycelium, and our heritage as an artist-founded company. Together with our Director of Communications, Ginevra Boralevi, they guide the partnerships that enable us to continue the artistic design explorations that Phil modelled. Through the power of ‘beauty’—and I put it in quotes to evoke all the desire, nostalgia, or uncanny recognition—we allow people to feel deeply connected to something. And that’s when you sell, right? It’s all about that connection.

Natsai Chieza: It doesn’t matter what it is.

Sophia Wang: It doesn’t matter what it is. You want to provoke people, and beauty is one way to do that. When I think about the history of Phil’s practice, he doesn’t necessarily speak in terms of beauty. He speaks in terms of the grotesque, the rotting, what becomes waste and then regenerates. There are early experiments with mycelium art objects that, by many accounts, were strange or uncanny—people didn’t know what they were looking at. To me, this is a more expansive sense of beauty that we work with at MycoWorks. Even with the perfect sheets of Reishi, there’s a story beneath the surface: this is from a fungus, this is mycelium. And then there are the sheets we leave unfinished, not perfectly smooth, with the strangeness, the signature, the grain of the mycelium—these elements inspire a sense of wonder or defamiliarisation. Both are, and are not, something I recognise. And that is the power of art, right?

It’s a formal balance that engages the senses—a kind of world that, for different people, might evoke nostalgic reverie, recall a dream, or suggest a possibility they had never considered. Or it might provoke discomfort, making them think, ‘What am I looking at?’—something that suddenly feels beyond words. This sensibility runs through our company, shaped by the artists who have come through and those we collaborate with to tell our stories. We continue to amplify the sense of wonder that Phil first tapped into when he saw the potential of mycelium—all the ways it expresses itself, both literally and symbolically. Like fermentation, once you start thinking about transformation, it becomes a powerful metaphor for how we see the world. And that, I think, is at the core of whatever optimism I have these days: the belief in the power to transform. Sometimes that means breaking things down and rebuilding. And you have to do it, because transformation demands reconstitution and redistribution.

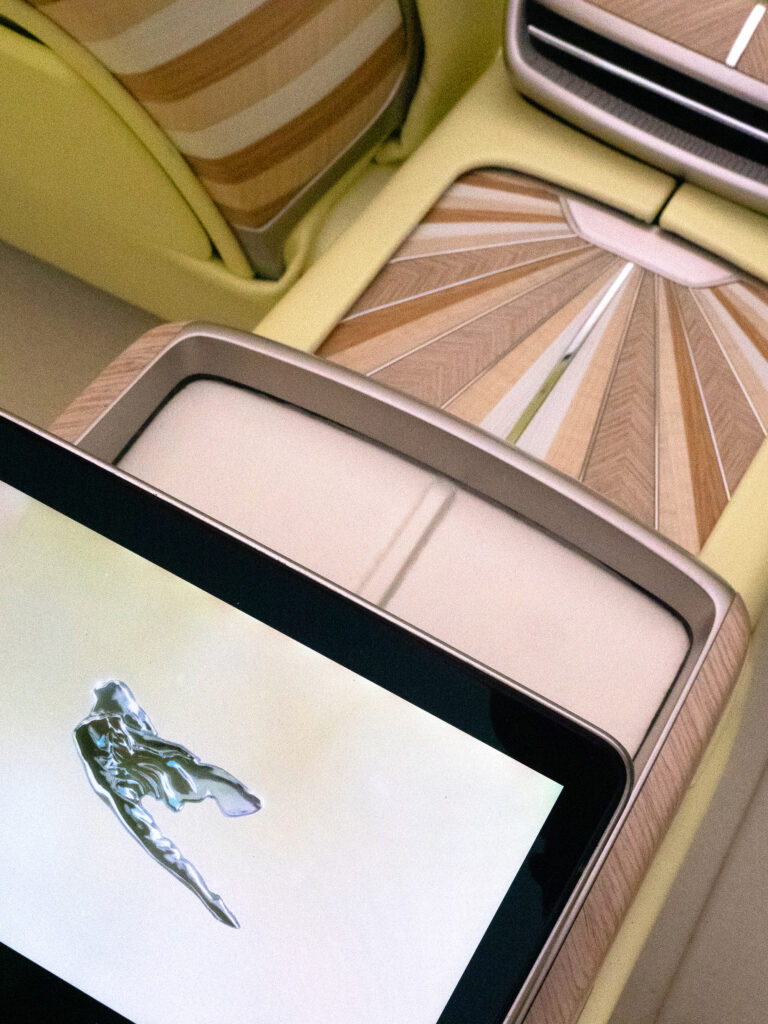

"Even in our earliest connection with Hermès, their Material Innovation Lead visited our basement lab—built with plywood and plastic sheeting—and saw a material that clearly engaged with the concept of leather but emerged from an art practice. We connected early on with a brand that understands the power of story, heritage, tradition, and craft."

Natsai Chieza: Given your distinctive world of view at Mycoworks, how do you think about commercial partnerships and special projects?

Sophia Wang: I think part of what set us apart from the beginning is how unconventional we are—a biotechnology company founded by artists. That has always been a kind of currency for us. We’ve embraced our unusual story because it deserves to be told. Even in our earliest connection with Hermes, their Material Innovation Lead visited our basement lab—built with plywood and plastic sheeting—and saw a material that clearly engaged with the concept of leather but emerged from an art practice. We connected early on with a brand that understands the power of story, heritage, tradition, and craft. Looking back, we were lucky to get on the right track early in shaping our identity as a company. We realised that it comes from authentically telling the story of the craftspeople, artists, design, care, and materials that define our work—and having the patience to go on that journey. Making something of quality is built on deep knowledge, craft traditions and expertise, and sustaining that value takes time.

As the company has grown, we’ve entered a phase where we work with a broad range of partners—whether large corporations or independent designers. A great example is the Mycelium Muse [t. - 11] project from last year, where we collaborated with seven independent female designers to create beautiful interior design objects. For us, ensuring that we are values-aligned with our partners is essential. The story we tell together has to make sense.

A clear example of what we don’t do—something common in the innovation space—is pushing material claims like ‘it’s vegan’ or ‘it’s sustainable.’ While those qualities may be true, the way such stories are told today often overlooks what we prioritise: beauty, quality, craft, heritage, and longevity. These are qualities typically associated with elite, high-end, or rarefied objects—the same language that surrounds art. We’ve embraced this approach because it’s also the language of our partners. At the end of the day, aligning values with our partners isn’t just a preference; it’s fundamental. And to me, that shouldn’t be unique—it’s how all partnerships should work. If you’re truly collaborating, you have to share both values and a common way of talking about what you’re creating.

Of course, there’s also the pragmatic side of where we are as a company. Any partnership has to make sense in terms of the scale we’re working at, the markets we’re addressing, and the calibre of the collaboration itself. It’s a highly discerning and selective process. This is an especially interesting moment for us because we’ve just launched our e-commerce site, allowing anyone to buy a sheet of our mycelium leather. This has been a dream since day one—to make our material accessible to all. And now, we’ve finally reached that point, thanks to our production facility in South Carolina, which is now operating at a scale that makes this possible.

SCALING DREAMS, SEEDING FUTURES

Natsai Chieza: Your approach feels novel and exciting. By making the material available for anyone to buy, you’re not operating purely B2B—you’re opening it up to everyone. That’s significant. I often speak with industrial designers who are waiting for materials to become available, with little concern for the development process. That mindset used to frustrate me because bridging the gap between design and development means we can spec materials faster and more meaningfully, based on real-world needs. But now I see it differently. There will always be people who just want the right material and the right time for the specified use case, and that’s ok too! The real question is once scale is no longer the issue, what is the right interface for better accessibility, no matter the approach.

Being able to offer this locally adds another layer of value. From a supply chain perspective, you’re not abstracted from the customer—they know exactly who they’re buying from. That kind of proximity can be powerful in building trust and encouraging wider adoption of biomaterials.

Sophia Wang: We’ve always wanted to work directly with designers, craftspeople, and artists. But there was a pivotal moment in our growth when we had to focus intensely on specific partnerships to scale with them and produce the volumes we needed to survive as a company. Now that we’ve reached the point where we can offer our material more broadly, it feels incredibly fulfilling. It feels like this is the vision we’ve always had—to make it available to everyone.

Natsai Chieza: What excites you about the future of mycelium? What’s on the horizon that we can’t yet fully see due to the realities of today, but could be possible in the future?

Sophia Wang: I think we’re already seeing glimpses of that future. And here I’ll go a bit off-script from Mycoworks and into the realm of Phil’s work with Open Fung. Mycelium isn’t just a material with extraordinary physical properties—it also interacts with its environment in transformative ways. Whether it’s bioremediation or genetic expression, our understanding of what mycelium is and can do is still deepening.

At Mycoworks, our entry point has been fashion—through Reishi, a material that allows people to physically engage with something entirely new: a ‘leather-not-leather’ rooted in biology. That tactile, emotional connection is important. It’s a gateway to broader possibilities. What I imagine on the horizon is a continuation of this path, where fashion opens the door and leads to further applications—bioremediation, ecological restoration, and fermentation-based systems for industrial use.

While we’re focused on scaling a very specific platform, I know there are others planting seeds in parallel directions. That’s what excites me: the multiplicity of futures growing from this one starting point.

Natsai Chieza: I know you’re close to Phil and his work. Could you tell us more about Open Fung?

Sophia Wang: Yes—Phil, along with several co-founders, including biotechnologists and someone from the Bay Area arts scene, began Open Fung as a way to build on the momentum we’ve seen in the field. Mycelium technology is still so new, and the knowledge base is incredibly dispersed—there might be a mycologist in South America working on one application, a materials expert in Amsterdam exploring another.

Open Fung brings those threads together. It’s a nonprofit that serves as a hub for research and access to mycelium technologies. They’re approaching it from all sides—from molecular genetics to artistic collaborations—always with a focus on open access and community-driven biology.

I don’t know the full details of their business model, but the spirit is clear: it’s about expanding the horizon of what’s possible with mycelium, beyond any one company or product. At Mycoworks, we’re focused on refining and scaling one application. Open Fung complements that by holding space for the broader exploration—creating the conditions for the ecosystem itself to grow.

Natsai Chieza: I love that mycelium has been a catalyst for all sorts of different models and that more continue to emerge. And it’s so essential for us to have an ecosystem where folks are both trying to scale technologies for specific applications alongside those trying to unearth what other potential lies beneath.

Sophia Wang: We need a diversity of tactics. We’ve identified the tension we’re navigating right now: working with brands like Hermes while also selling sheets directly to anyone on our site. The guiding principle is that ‘technology should be for everyone,’ and we follow certain paths to make that possible. I’m really excited that initiatives like Open Fung exist, and there are other similar projects around the world, of course. These initiatives are in the open science spirit, which is exactly what we need. That vision has always been fundamental to Mycoworks from the start—‘this should be available to everyone.’ But as you build a corporation, you inevitably have to build these walls in order to survive along the way.

"The key is generosity in this space. You can’t be overly acquisitive or territorial, wanting to be the only one doing it. You have to rely on the knowledge of the entire community of innovators and engineers. Of course, you want to lead the way for whatever reasons you have, but there needs to be an expansiveness in how this is approached for it to work."

Natsai Chieza: Over the last couple of years the biotechnology sector has been in the midst of what some may describe as a market correction. We’ve seen a lot of leading examples—particularly those advancing synthetic biology—have to come to terms with seemingly immovable challenges by pivoting, reducing scope and in worst cases ceasing to operate entirely. And yet it’s also true that these technologies and the resulting ecosystem of knowledge, culture and biology—are not going away any time soon. So how do we carry ourselves forward, continuing to do impactful work while remaining optimistic? What can success look like?

Sophia Wang: One way I’ve come to think about this is that we’ve already succeeded. Mycelium technology wasn’t even a thing 10-15 years ago. It was emerging. We had companies like Ecovative, who were actually founded before us, and then Bolt Threads, and now there are many companies around the world working with it. But back then, it wasn’t something people were really talking about. Now, it’s real, because you have a community of researchers, entrepreneurs, artists, designers, and scientists all pushing this technology forward. A new technology isn’t advanced by just one player; it’s advanced by a collaborative community. That being said, there still needs to be a demonstration model of feasibility and scalability.

I know there are a lot of hopes and dreams tied to Mycoworks succeeding in this space. I hear it all the time—people say, ‘You have to do it for us. You have to show that it can be done.’ So, I am optimistic because we’ve come this far. We have a plant that can produce millions of square feet of material each year, and it’s performing well and meeting its targets. We’re scaling up production. No one knows exactly what the future holds, and it might take different forms or involve different players. But I share your optimism that this is here, and now it’s just about pushing it forward.

The key is generosity in this space. You can’t be overly acquisitive or territorial, wanting to be the only one doing it. You have to rely on the knowledge of the entire community of innovators and engineers. Of course, you want to lead the way for whatever reasons you have, but there needs to be an expansiveness in how this is approached for it to work. Mycoworks has brought it this far, and I hope we keep moving forward. But if the path changes, I know this technology will still carry on.

Natsai Chieza: I think that’s an amazing place to end.