Biodesign Meets AI: Making Space for

More-than-Human Intelligences

Orkan Telhan, an artist, designer, engineer, and the Chief Information and Data Officer at Ecovative—In conversation with Natsai Audrey Chieza

RE-THINKING WITH TECHNOLOGY

Natsai Chieza: We’re having this conversation remotely and you’re calling in from a mushroom farm in Ontario. Naturally, I’m intrigued and would love to hear more about your background and the path that has led you here. What inspired your journey to becoming a pioneering leader in biodesign?

Orkan Telhan: I have always been interested in how technology shapes society—not necessarily in a positive, world-saving sense, but with a critical perspective: “What kind of problems will it create, and how will society respond?” I went to graphic design school first before quickly transitioning to product design, focusing on both software and hardware. That’s when I became highly technical, learning to build robotics, virtual reality systems, and more: the design process involved many different elements. Later, I pursued a PhD in design and computation at an architecture school, which gave me a new lens to examine the world. It was a type of architectural education that wasn’t just about training architects, but about fostering an architectural sensitivity and sensibility in the world. Now, I find myself as an engineer and a technical leader in the biodesign space, continuing to explore these questions from a different vantage point.

As a consequence of my background, I have a specific approach to working with technology: I either modify existing technologies or create new ones, using them as my medium of expression. The issues and questions that drive my process are crucial—whether it’s sustainability, environmental change, xenophobia, immigration, gentrification, or colonisation. These are problems we often overlook when discussing technology design, even though they’re right in front of us. This is where my artistic perspective comes in: I enjoy asking these difficult questions and addressing them through my work.

“ I have a specific approach to working with technology: I either modify existing technologies or create new ones, using them as my medium of expression.”

Natsai Chieza: I’m curious—how much does your architectural background influence what you do today?

Orkan Telhan: That’s an interesting question because, for me, the answer is quite straightforward—I literally design incubators or growth rooms for non-humans. Sometimes it’s bacteria, sometimes it’s mycelium. So, in a very literal sense, I’m creating controlled environments or “architecting” spaces for growth, with climate controls and all. It’s engineering space or designing environments for species other than humans. Architecture, as a discipline, is so human-centric—it’s fundamentally focused on human needs. There’s so much potential in creating architecture for non-humans, but that’s a different conversation altogether!

Conceptually, though, my work also questions why we always build externally, outside the human body. My PhD explored why architecture is so fixated on creating enclosures around us—why not design within the human body? That’s what led me to biology and synthetic biology: the idea that the body’s interior could also be an architectural space, a design environment that traditional architecture tends to overlook entirely.

Natsai Chieza: Can you give us some insight into the kinds of research questions you’re exploring right now?

Orkan Telhan: There are several fascinating directions here that I’m still exploring—particularly the microbiome. To me, the gut is an incredibly significant and contested space. It’s constantly influenced, almost colonised, by the foods we consume and the environments we inhabit. The bacteria in our gut reflect our origins and lifestyle, affecting everything from our mood to our gender identity. But when I first started, my focus wasn’t on the microbiome. I was looking at protocells, synthetic structures which you can introduce DNA into. I wondered, how could we “engineer” the body from within? Not just through genetic modification, but by introducing new capabilities that might be functional or even non-functional—qualities that could transform the body’s potential.

So, from protocells to the designer microbiomes, there’s an entire architectural space within the human body to consider—a “liquid” space, not the traditional solid structures we associate with architecture. I try to move beyond the traditional modernist view of “inside” versus “outside” the body. Rather than focusing solely on the visible, exterior body, I’m interested in the interior, which is largely non-human cells. This isn’t something architecture has traditionally addressed; that responsibility has been left to medicine, which deals with the body’s internal aspects because it has to “fix” things. But the idea of theorising the body’s inner architecture—exploring it beyond the medical lens—is almost untouched in the field of architecture.

Natsai Chieza: I love your perspective on theorising the human body—and you’re right it’s understood through the medical lens of parts and process, but less so on meaning. Have you come across other disciplines that explore the body’s interior beyond the mechanistic?

Orkan Telhan: Some philosophers do touch on these ideas in a way that changes how we think about interdisciplinarity. For example, philosophers like Baruch Spinoza, centuries ago, offered a radically different view of the body—not as flesh, but as something abstract, as rhythms of things with varying speeds coming together. This isn’t about the “inside” or “outside” of the body, but rather about a rhythmic flow of particles forming an interconnected space.

When we view the body this way—as a rhythm of particles—it transforms how we think about architecture, the microbiome, and design altogether. What I refer to as “liquid space” is really just one way of describing this beautiful interiority. It’s a perspective that moves beyond the boundaries of traditional physical forms and into a more profound, almost cosmic view of architecture within the body.

DESIGNING FOR MORE-THAN-HUMAN INTERACTIONS

Natsai Chieza: So, moving from design to biotech and now AI—what excites you about the confluence of these fields? As you journey between them, what happens at this Venn diagram intersection? And what do you see as the implications for the future of our planet?

Orkan Telhan: The Venn diagram is a useful way to frame this. I think of it as a continuum of non-human intelligence. For instance, I work with mycelium every day, and it has a level of sophistication that humans simply can’t replicate. The idea of humans as the benchmark for intelligence is outdated; there are many types of intelligence. This includes diverse forms of human intelligence, as seen in the neurobiological spectrum, and spans to different species and now even machine intelligence, whether silicon-based, algorithmic, or synthetic.

In this Venn diagram, we have different species, diverse human intelligences, and various types of synthetic intelligences. What’s fascinating is that humans don’t necessarily need to be in the centre of it all. Imagine a direct feedback loop between mycelium and a computer—these non-human intelligences could communicate without us being involved. And this interaction might evolve entirely new biological forms, ones not bound to human needs and desires.

In design, we’ve traditionally focused on addressing human needs, but this convergence offers a unique design space—one that fosters communication between different entities. Practically, I use these ideas daily at Ecovative. Algorithms help us understand mycelium behaviour in ways our human brains can’t, as we’re limited to thinking in three dimensions. But machine learning algorithms can process data from, say, twenty different sensors and learn from multiple dimensions simultaneously. This practical application of AI is essential because it allows us to understand complex biological behaviours that we otherwise couldn’t.

Natsai Chieza: What kind of interface enables this intersection? How are these different forms of intelligence communicating to create new possibilities? And could you share some of the practical benefits that emerge from these interactions? I know that some of the outcomes might not be human-centred, and we might not even fully grasp them, but from an ecological perspective, why might it be important for these different intelligences to connect?

Orkan Telhan: One of the most incredible forms of intelligence I’ve discovered through working with farmers is what I’d call “farmer’s intuition.” It’s this deep, sensory understanding they develop over years—whether they’re in a greenhouse, a field, or tending to mycelium. A farmer can look at soil, feel its texture, smell the plants, observe the sunlight, and just know what’s needed for growth or what might be off. This knowledge isn’t something an outsider like me can just read about; it’s a practised, embodied awareness built over thousands of years of agricultural practice. For example, centuries ago, Byzantine farming manuals [t. - 1] documented this kind of accumulated wisdom.

Now, with AI, we have another layer of “intuition”—machine intuition. Dozens of sensors can read conditions continuously, and deep neural networks process this data in ways that form a kind of machine “sense.” My role as a designer is to create an interface that allows the machine’s intuition to communicate with the farmer’s intuition. Sometimes, this might be a visual interface showing a graph or pattern change. Other times, it’s more direct—like a simple alert telling the farmer, “This organism at this stage needs more water.” The goal is to create an interface that farmers can act on practically, enhancing their ability to care for their crops in a meaningful way.

Farmers don’t just want information for the sake of knowledge; they need actionable insights to improve yield, quality, and conservation. So, the interface I designed builds a feedback loop between AI and the farmer’s intuition, enhancing the farmer’s natural relationship with their crops and fostering a deeper level of care.

Natsai Chieza: Your perspective hints at a deeper dialogue than the very blunt narratives framing the utility of AI at the moment—where, rather than only being seen as a tool acting autonomously to solve productivity issues to optimise output, you seem to suggest a higher purpose or order to integrating these intelligences is required.

Orkan Telhan: Absolutely—someone could challenge me and say, “But ultimately, isn’t the farmer’s goal to increase yields and profit?” And they’d be right; productivity is a core part of this. But my critical perspective here is to question what all this optimisation is really for. Is it just about producing more for human consumption, perpetuating extractive cycles that strain the planet? Or is it about showing that sustainable farming can exist—we can have bacon without killing millions of pigs every day.

This is why, at Ecovative, we’re focused on ensuring that these AI-driven efficiencies don’t just amplify consumption but instead help manage resources sustainably. AI can mitigate resource waste, helping us “produce more with less.” So, for me, it’s about bridging these goals: using AI not merely for higher yields but to meet production needs in a way that remains beneficial to the environment. This balance is essential if we want technology to support a regenerative rather than an extractive future.

“I caution against design fetishisation—mycelium is more than just interesting forms or material. Designers must consider the entire supply chain and scalability to ensure these materials work outside the studio and on the farm. From nanomanufacturing to customer-ready products, making the whole continuum ethical, accountable, and sustainable is a design challenge.”

FORM FOLLOWS SYSTEM

Natsai Chieza: You’re currently on a farm, which offers a beautiful insight into how we envision the scale-up of mycelium agriculture. Could you share a bit about where you are, what brought you there, and how mycelium cultivation connects with the land?

Orkan Telhan: I’m currently at Whitecrest Farm in London, Ontario, one of our growers to scale out mycelium bacon. While our research facility is in Green Island, New York, Whitecrest has a unique role as a traditional mushroom farm transitioning into a mycelium-focused operation. Mycelium, often called the vegetative part or “root” of the mushroom, differs significantly in growth and structure from mushrooms, which are the fruiting bodies. Our goal here is to cultivate mycelium into a fluffy tissue that can then be processed into bacon—a product now available in over a thousand stores, with a full list at myforestfoods.com.

What excites me as a designer is seeing this journey from lab research to a tangible product on supermarket shelves. It’s no longer just a scientific experiment; it’s a commercial, scalable crop. This isn’t something you’d find in nature—mycelium doesn’t naturally grow in the aerial form [t. - 2] we need—so we’re creating new processes to produce it at scale. Whitecrest and other farms are learning to cultivate this new crop, much like early farming with corn or beans, but with mycelium as a truly novel agricultural product.

This shift also means helping farmers build an intuition for mycelium growth. While they have generations of expertise with mushrooms, mycelium cultivation requires different insights, which we’re developing together using algorithms and interfaces to support their understanding and care for this new crop. It’s a fascinating blend of traditional farming wisdom and cutting-edge technology, all contributing to a product that can help redefine plant-based foods.

Natsai Chieza: How different are the farms relative to context? Are there different characteristics to a farm growing mycelium bacon vs. mycelium textiles?

Orkan Telhan: We work with multiple farms beyond Whitecrest. For example, our mycelium textiles involve a different farm in the Netherlands. We prefer to work with Dutch-style farms. In the mushroom industry, “Dutch-style” refers to farms with specific shelving structures—it’s a fairly common system, so many farms can adjust their infrastructure with minimal change.

A key priority for us is retrofitting existing farms instead of building new ones from scratch. By adding basic technologies to established farms, we avoid the high costs of creating new facilities and make the whole process more sustainable. Whitecrest, for instance, is relatively close to Albany, which helps with resource access and logistics.

Our farm choices are also influenced by various factors—access to resources, labour, and regional economics all play a role. Deciding between farms in North America, Europe, or other regions involves considerations of supply chain priorities and business strategy, especially as we aim for supermarket-scale production. It’s a complex process, but this approach helps us create a sustainable, scalable solution for bringing mycelium products to the market. Sustainable businesses can only exist in sustainable business, those that can pay for themselves.

Natsai Chieza: That’s where I see the tension. Biotech promises innovation, yet its business model often centres on “drop-in” replacements that fit within existing infrastructures and economic models. Take the food system, for example, which is built around industrial agriculture with the supermarket as the main distribution point. Suddenly, we have this powerful technology that could redefine our relationship with the planet, but it’s constrained by the socio-cultural and political frameworks of today.

Mushroom farming has been around for ages, and now we have this potentially game-changing technology that’s being treated as yet another commodity. I know you’re asked about this often, but I’m curious how you personally navigate this tension. I know you’re deeply invested in ensuring that scaling up mycelium doesn’t lead to monocultures or detrimental impacts. How do you balance these forces in your work?

Orkan Telhan: Absolutely, that tension is crucial, and as a designer, I sometimes feel frustrated by the gatekeeping in these industries. In food, it’s one type of gatekeeping, but in textiles, where we’re developing mycelium-based materials, it’s different. Interestingly enough, people can be more experimental with their food choices than their clothing. For example, we don’t yet have a commercially available product like mycelium leather in stores, but mycelium bacon is further along.

When I joined Ecovative, I came in on the research side of the textile division, which has been fascinating. Mycelium leather is often compared to animal leather, which is so cheap and functional, and I hear the same question over and over—“why even try to replace it?” Animals are already being raised for food, so hides are available as a byproduct. But personally, I want to create something impactful within my lifetime, and that drive pushes me to keep refining this material despite these challenges. No animal should die for food or their skin.

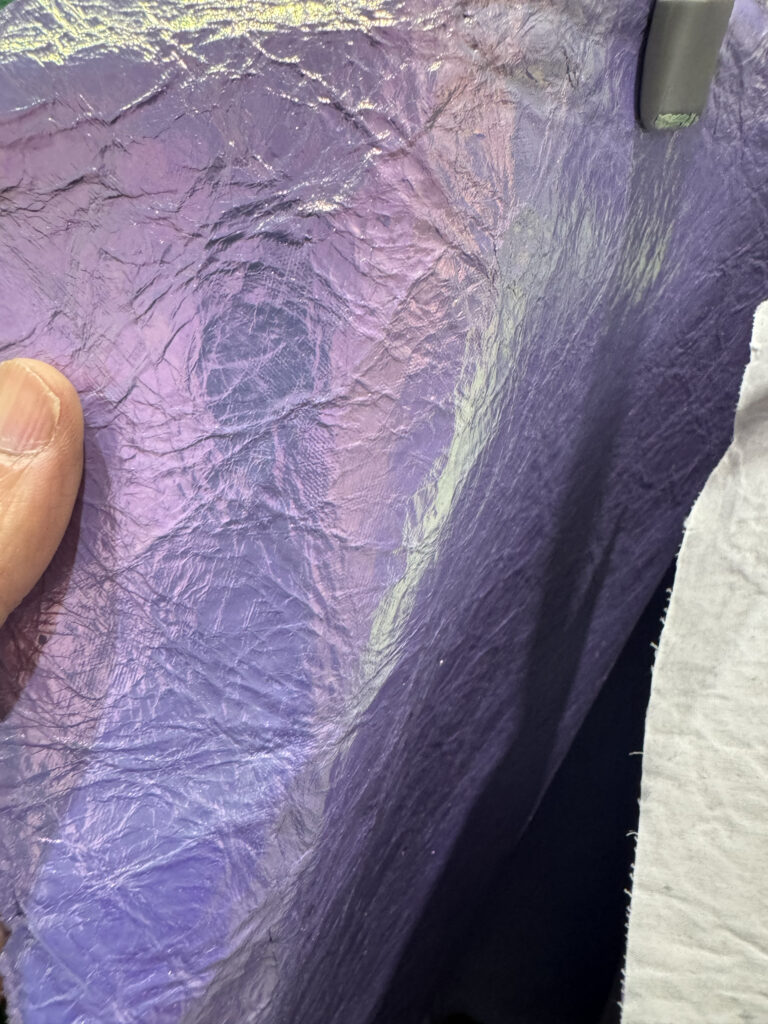

We put every aspect of mycelium leather through rigorous testing to meet the demands of the leather industry, and we’ve made huge improvements. But sometimes I wonder—why aren’t there more designers willing to work with this material as it is to showcase its unique qualities? You and I are designers; we know it’s about showing the consumer that this material has its own beauty, even if it might not last as long as traditional leather. It’s compostable, cruelty-free, and has other unique affordances.

There’s a certain hypocrisy, though. People say they want sustainable options, but they also expect the same qualities they’re accustomed to. Interestingly, through this process, I’ve gained a real respect for the natural qualities of leather itself—millions of years of animal evolution have created an extraordinary material. We can’t truly imitate that; at best, we can approximate or create something new entirely. So, our goal is not to replicate leather but to develop a distinct material with its own design language, one that consumers can appreciate for what it uniquely offers.

Natsai Chieza: This tension is something anyone in this field must feel, given the social, economic, and geopolitical realities of scaling biotechnologies. In the process of scaling up and building out vital infrastructure, are we already locking ourselves into specific commercial relationships between suppliers and end-users that may prevent other stakeholders from collaborating as co-creators in shaping the systems and models for the bioeconomy?

Orkan Telhan: Exactly, this tension is significant. For instance, with mycelium textiles, we can grow them at scale, which is hugely beneficial environmentally. Unlike cattle, which take years and enormous resources to produce hides, mycelium can be grown in large quantities within a little over a week. But here’s the challenge—it’s like the “ugly produce” problem. People want uniform, flawless leather, but mycelium has natural variances. Just like a wonky tomato, a mycelium hide may have small imperfections, which the market currently resists. If we could normalise these “imperfections,” we’d reduce waste and make the system more sustainable.

The scalability of mycelium is promising because it’s close to what I’d call a sustainable scalability model. Unlike fermentation-based materials, which face challenges scaling solid materials, solid-state cultivation of mycelium [t. - 3] , like mushroom farming, is much closer to feasible scaling. I’m optimistic, though it will take time to perfect.

As someone who’s seen biodesign evolve from the early days, I find mycelium incredibly versatile. It’s a fabrication platform at the nano- and macro-scale. By controlling the growth of hyphae, we can create fibres, tissues, and even foams, opening possibilities from packaging to textiles. But I caution against design fetishisation—mycelium is more than just interesting forms or material. Designers must consider the entire supply chain and scalability to ensure these materials work outside the studio and on the farm. From nanomanufacturing to customer-ready products, making the whole continuum ethical, accountable, and sustainable is a design challenge.

I joined Ecovative not as a designer but to support engineering and science teams, and now I oversee data and AI. But at heart, I’m a designer who designs systems, and I see the entire process—from nano-level fabrication to commercialisation—as a design problem where engineering plays a crucial role. This journey has only deepened my appreciation for the engineering involved in biodesign.

“The open-door approach is about moving beyond compartmentalisation—raw materials need to get into the hands of designers. We need more designers who understand how to work with and even grow these materials.”

MINDS FROM EVERY FIELD

Natsai Chieza: I’ve noticed a tendency for American biotech companies to readily embrace unique talents like yours. It feels very in tune with the interdisciplinary spirit of biotechnology and synthetic biology—where engineering, science, and art and design come together in novel ways. It’s wonderful that someone building out engineering and AI capabilities at Ecovative also brings a critical perspective rooted in the humanities. I think recognising different forms of human intelligence is crucial to understanding and shaping what we’re building. I’d imagine it’s not just you—that other team members bring diverse perspectives as well.

Orkan Telhan: Yes, there are people like our Principal Scientist and Head of Bioprocess Design at Ecovative, Jake Winiski, with whom I have been working very closely since I started. He knows everything about aerial mycelium and has an MFA degree. He learned it all hands-on at the bench, blending art and science in a way that’s truly inspiring. Another great example is our Director of Process Engineering, who oversees the large-scale farm builds—he also has a BFA. And our CTO is an accomplished painter. This artistic influence isn’t just an add-on; it’s truly woven into the DNA of the company. It’s not about having one or two unique individuals—it’s about genuinely valuing and integrating that artistic perspective.

Natsai Chieza: As a company, you’ve externalised this ethos. Ecovative also has an open-door policy for artists and designers. Could you talk a bit about that?

Orkan Telhan: Our Grow-It-Yourself (GYI) [t. - 4] initiative is an excellent example of that open-door approach. Not everyone realises it, but this is an Ecovative initiative led by our brand manager, Grace Knight, who also is an accomplished product designer. Many students in architecture and product design schools are experimenting with our materials, especially since some patents in Europe have been lifted, allowing for more open use there. Our fashion programme also works closely with designers to supply mycelium textiles for creative projects.

The open-door approach is about moving beyond compartmentalisation—raw materials need to get into the hands of designers. We need more designers who understand how to work with and even grow these materials. That’s something I admire in your work as well—you’ve always gone beyond using pre-dyed pigments, investing deeply in the entire process to create something original. You’ve helped shape the field by showing designers they can engage with these materials from within rather than relying solely on scientists for information. It’s a powerful way to break boundaries and innovate.

Natsai Chieza: Thank you. I appreciate that, and you’re right. It’s that hands-on learning from the bench that’s so essential. We need more institutions that make this kind of access a reality. Then, we have a critical mass, and new things can emerge. Alright, one last question. If you could, what advice would you give your younger self?

Orkan Telhan: My younger self… Well, looking back, each stage of my life led naturally to the next, so it’s hard to say I’d redesign anything. Recently, I read something about Gottfried Wilhelm Leibniz—he started as a lawyer before becoming a mathematician much later in life. They say that Leibniz’s “problem” was that he had met with lawyers first before he met mathematicians, which is why he spent so many years in law prior to inventing calculus and laying the groundwork for digital computers over 100 years ago. I sometimes wonder if I spent too much time in academia, but then again, academia—my students, my colleagues—shaped who I am. I think if there’s one thing I’d tell my younger self, it’s to be intellectually brave sooner. I spent years worrying about what I didn’t know, trying to catch up before allowing myself to dive in. I was always waiting to be “ready.” I only started taking big risks later—leaving my tenured university position, for instance, to work with mycelium at Ecovative.

If I’d been braver in my 30s, my path might have looked different. But in the end, everything flows where it’s meant to, and I’m at peace with the journey.

Natsai Chieza: That resonates. In the past, I found that learning through hands-on experience often pulled me between two worlds: “Should I do a science PhD to understand this fully?” and then, after six months in the lab, I found myself yearning for design, feeling like I was missing something there. In this culture, being in between worlds—science and design—with both conviction and humility can feel like a tug of war, and I still find it challenging at times.

Orkan Telhan: And now, with tools like ChatGPT and various AI agents, the way we access knowledge has transformed. The sheer amount of information AI provides daily is incredible. I’m not suggesting AI replaces a PhD, but if I were pursuing one now, I’d be using an AI agent constantly to explore questions. At Ecovative, we’ve integrated AI into our processes so people can query our institutional knowledge on aerial mycelium—a knowledge base that doesn’t exist outside our company, as we don’t publish much of our internal research. AI helps us mine this knowledge and, importantly, revisit past work—like checking if we tried a particular strain 15 years ago. It’s not just learning in the traditional sense but relearning and refining what we already know, as humans naturally forget over time.

Natsai Chieza: Reflecting on everything we’ve covered—integrating different intelligences, building intuitive practices, and the role of AI in capturing and evolving institutional knowledge—it feels like we’re seeing the emergence of a new paradigm in how we understand and shape these fields. I’m genuinely inspired by your work and the perspectives you bring, and I’d be thrilled to continue this conversation in the future as these technologies and practices evolve. Thank you for such a rich and thought-provoking dialogue.