A chocolate industry without child slavery and environmental destruction is possible.

And it all starts with ditching cocoa.

In America, most chocolate is made with oxidised milk powder, lending it a flavour that Europeans liken to baby vomit. But their friends across the pond seem to enjoy it just fine. While the biggest producers of chocolate around the world will permit almost endless variation in their recipes, the one key ingredient they all insist on is cocoa, and that’s a problem.

Cocoa is a cash crop bound up in all sorts of global issues. Unlike the meat or dairy industry, where concerns around ethics and sustainability have been cemented in the public consciousness over recent years, the widespread malpractice that permeates the world of chocolate remains largely unpublicised. But it still exists, and in fact is often worse than the meat and dairy industry. For example, 55% more water is used in chocolate production than beef production (it takes 27,000 litres of water to produce a kilo of cocoa beans), and 11 times more greenhouse gases are emitted by dark chocolate production than cow’s milk production.

In Ghana and the Ivory Coast, where two-thirds of the world’s chocolate is grown, there are estimated to be 1.5 million child labourers working in the chocolate industry, many of whom have been illegally trafficked from neighbouring countries. To meet growing global demand for chocolate, great swathes of West African rainforest have been destroyed to make way for cocoa plantations: since 1990, 80% of forested land in the Ivory Coast has disappeared. This kind of activity, of course, drives climate change and changes local weather patterns, so the cacao that’s planted in uniform monocultures is more susceptible to disease. When crops fail, new areas of rainforest are cleared for new monoculture cacao plantations, perpetuating the cycle and further exacerbating the problem.

Past experience means that both chocolate corporations and national governments should know better by now. In the late 1980s, witches’-broom disease swept through Brazil’s cacao plantations, eradicating around 70% of the country’s crop and inflicting economic and social catastrophe. Brazil went from being one of the world’s largest exporters of cacao beans to a net importer. The same could happen in Ghana or the Ivory Coast if practices don’t change.

While there are now numerous independent chocolate companies working to improve the way cocoa is farmed both from an ecological and human rights perspective, ten multinational companies that we all know the names of still have a vice-like grip on the farm gate price of cocoa, which means that meaningful change within the industry can only happen if the big ten are onboard – and they’re dragging their heels.

This is not only a problem of monopolistic industry but also of public perception. When consumers think of the “best” chocolate in the world, it’s not Brazil, Ghana and the Ivory Coast they think of, it’s Belgium, Switzerland, Italy, and maybe Ecuador at a push. The origin of the product has been intentionally dislocated from our minds. And while we now have strong associations with origin and terroir for coffees, wines and cheeses, the world of chocolate is still a long way behind.

Thankfully, change doesn’t have to mean making incremental fixes to a giant, slow-moving beast. Change can also mean bypassing the most problematic parts of it altogether. What if great chocolate didn’t have to have anything to do with a broken industry under monopolistic control? What if great chocolate didn’t have to have anything to do with cocoa at all?

That question drives everything we’re doing at WNWN Food Labs, the first company ever to bring cocoa-free chocolate to market. We use cutting-edge science to convert sustainable, plant-based ingredients into a delicious cocoa-free chocolate that snaps, tastes and melts just like conventional chocolate. We source widely-available plant-based ingredients with responsible and sustainable supply chains and harness cutting-edge science to unlock their flavour potential, meaning we don’t have to use any cocoa in our “choc” at all.

Weirdly, it all started with a bare fridge and some old potatoes. I was staying at my parents’ house and cooking up a bit of dinner. Some old potatoes were on the boil and, as I stuck my head over the saucepan to check on them, the steam that billowed out smelled of hot chocolate. This got me thinking, “What is it that makes chocolate chocolate?”

“Chocolatey flavours aren’t unique to chocolate, and we’ve dug into nature to find ways to extract them from other, more ethical ingredients.”

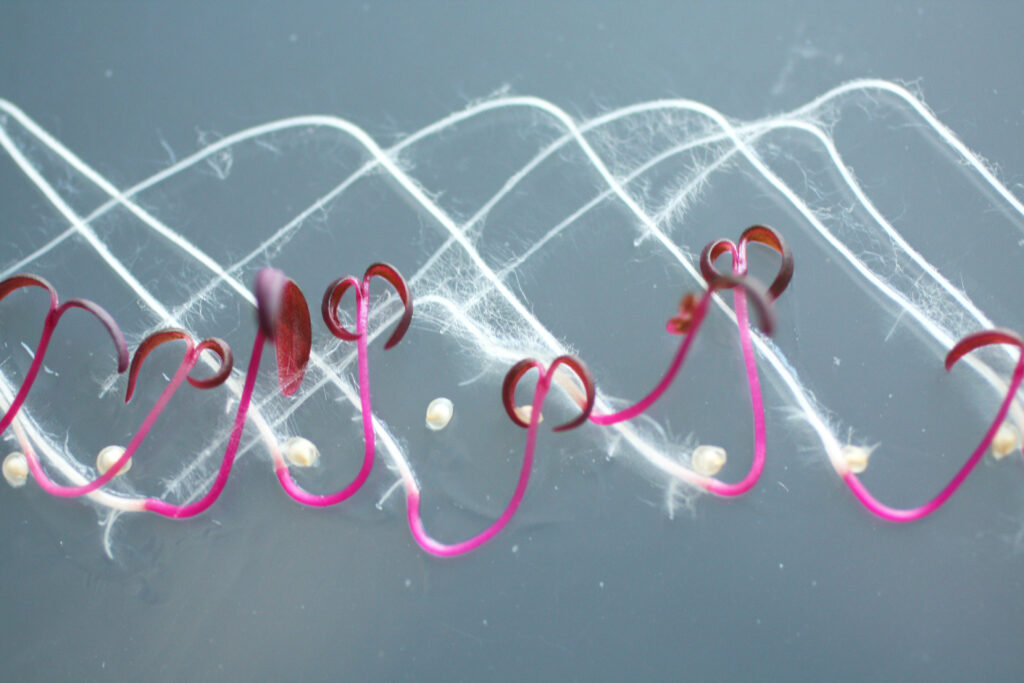

It’s actually quite a specific set of ingredients and processes: cocoa beans are fermented and then roasted, which creates the flavour profile we all know and love. More specifically, microorganisms break down sugars in the cocoa, which create “flavour precursors”. When these precursors are roasted it creates a rich three-dimensional chocolatey flavour — one of a handful of flavours that the world is addicted to. These precursors and flavours aren’t unique to chocolate, and we’ve dug into nature to find ways to tease them out from other, more ethical ingredients. We discovered you can use the magic of microorganisms to create the same flavour precursors from legumes and cereals like carob and barley before roasting them to create a flavour that’s just like chocolate. (I call this the science of delicious brown stuff.)

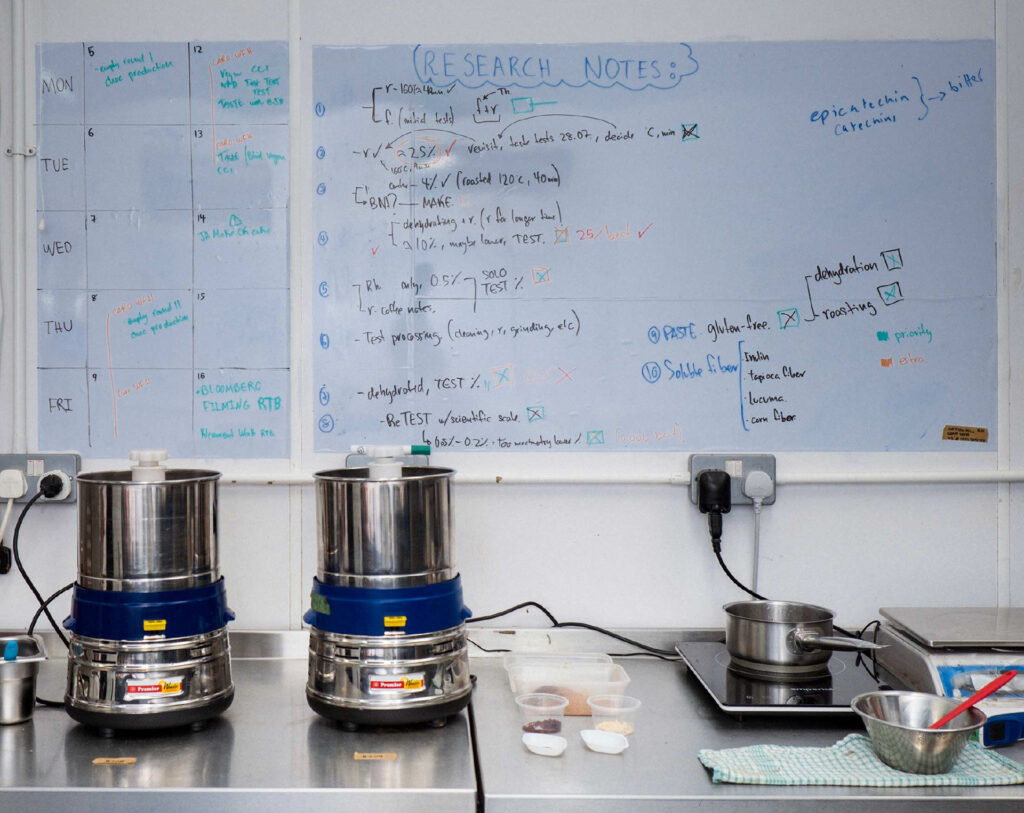

It may sound simple enough, but it’s taken us a long time to get to the point where we have a product that tastes just like chocolate — that smells and snaps and melts and lingers on the palate like the real thing — without using any of the same problematic ingredients. Part of our work has been to use nature to bring out new flavours, but another has been to interrogate farming practices and global supply chains. We use barley because of its sustainability credentials and the ease with which it can be grown across northern Europe. We use carob for its antioxidant profile, similar to what you’d find in good-quality cocoa. It’s also a plant that thrives in brackish soils (those closer to salt water) and has an incredible ability to sequester carbon as it grows.

To replace cocoa butter in our bars we’ve landed on using shea, a nut fat that’s also grown in West Africa. We’re working with a credible producer with a transparent, slavery-free supply chain that supports the local communities where the shea is grown and is typically processed by groups of women. All of this means that the “choc” we produce uses 90% less water and emits 80-90% less greenhouse gases than any other bar of regular chocolate on the market. By creating alternatives that wean “Big Choc” off their dependence on a single crop from a very small geographic region in the global south, we believe we can loosen the grip those chocolate multinationals have on that area and its people.

Another key benefit of the approach is that understanding what makes things taste “chocolatey” and “more chocolatey” could be powerfully shared back to cocoa-growing regions to reduce waste, improve product yield and increase the amount of money in farmer’s pockets. For example, much of the flavour of a final cocoa bean comes from the fermentation, a spontaneous, complex and nuanced cascade of reactions mediated by multiple species of microorganism. Expertise in cocoa fermentation can reduce waste in the form of incompletely fermented beans, thus improving the yield of beans that farmers are able to sell. Moreover, beans fermented to yield more of the flavour compounds that chocolate producers want can fetch higher prices. Insights from cocoa-free research and fermentation education could therefore be a powerful added value to cocoa farmers. We’re also creating markets for non-cocoa ingredients that grow in those regions, around which new, more equitable, economic models, free from the implications and restrictions of the cocoa industry, can be built.

The reality, of course, is that most startups fail. So, if we don’t make it, we want to ensure that WNWN leaves some kind of legacy behind. Right now we have a platform because what we’re doing is weird, and it’s important that we use that platform to educate consumers about the problems that exist in the cocoa supply chain. Even if we fail at everything else, at least we’ll have contributed positively to that.

Dr Johnny Drain is a leading global expert on fermentation and the co-founder of WNWN Food Labs.